An East German in the City of Archbishops

Notes From Braga about religion, identity and nationhood

“Portugal is still a very Catholic country,” I was told over lunch yesterday. Around 80 percent of the population here define as Catholic. Though regular church attendance is much lower, the cultural dominance of Catholicism remains. This is especially true where I am at the moment — in Braga in northern Portugal, known as the “City of Archbishops”.

The irony of coming here, of all places, to talk about the GDR hasn’t escaped me. Coming from eastern Germany, a region not just majority secular but majority-atheist, so much so that it’s been dubbed “the most godless place on Earth”, I was fascinated by it all. What do religious roots, even as they dwindle, do to national identity and social cohesion?

As the oldest Portuguese archdiocese, Braga is home to numerous ornate churches and other religious sites. As I explored them, I began to ponder Germany’s unique religious landscape. Parts of Germany can also be described as “still very Catholic”, but unlike Portugal, it has never had a majority Catholic identity as a country. I wondered what the patchwork nature of Germany’s religious composition has done to its outlook as a nation and whether that still matters today in an increasingly secularised world.

My Portuguese publishers took me on a trip outside of Braga to its famous Sanctuary of Bom Jesus do Monte, a Catholic shrine and pilgrimage site reached by a distinctive Baroque stairway or via he oldest funicular in the world moved by water balancing (a sucker for both technology and elaborate stairs, I insisted on trying both). On the way out, the taxi driver, a proud local man with a flat cap and more stories to tell than fitted into the short journey, regaled us with tales of Braga’s religious importance. Its archbishop, the man boasted, was so powerful that “only the Pope can tell him what to do.”

I confessed to my hosts, who had invited me over to give a dozen or so press interviews about the Portuguese edition of Beyond the Wall, that as someone raised in a world uniquely devoid of religion, I’ve always had a particular fascination with religious buildings, rituals and culture. Where I grew up, in rural Brandenburg to the east of Berlin, churches, by and large, were often repurposed as community centres or libraries.

As a child, it was fascinating for me to visit places like Bavaria, where fellow Germans lived entirely different lives. Elaborate churches were tourist attractions to me, but active places of worship to the locals. I once attended a Catholic funeral in western Thuringia, and it felt to me like stepping back in time, from the ancient village church with its thick stone walls to the singing, incense and rosaries.

Due to its history, Germany ended up with a unique religious landscape. First, there is the Protestant-Catholic divide, which began in the early 1500s, when Martin Luther challenged the Catholic Church and sparked the Protestant Reformation. There was no German state yet, just a collection of principalities, most of which were loosely held together within the Holy Roman Empire. Some princes in the German-speaking lands embraced Luther’s ideas because they saw a chance to assert their own power or believed in the reforms. Others remained Catholic due to stronger ties to Rome and the influence of Catholic rulers.

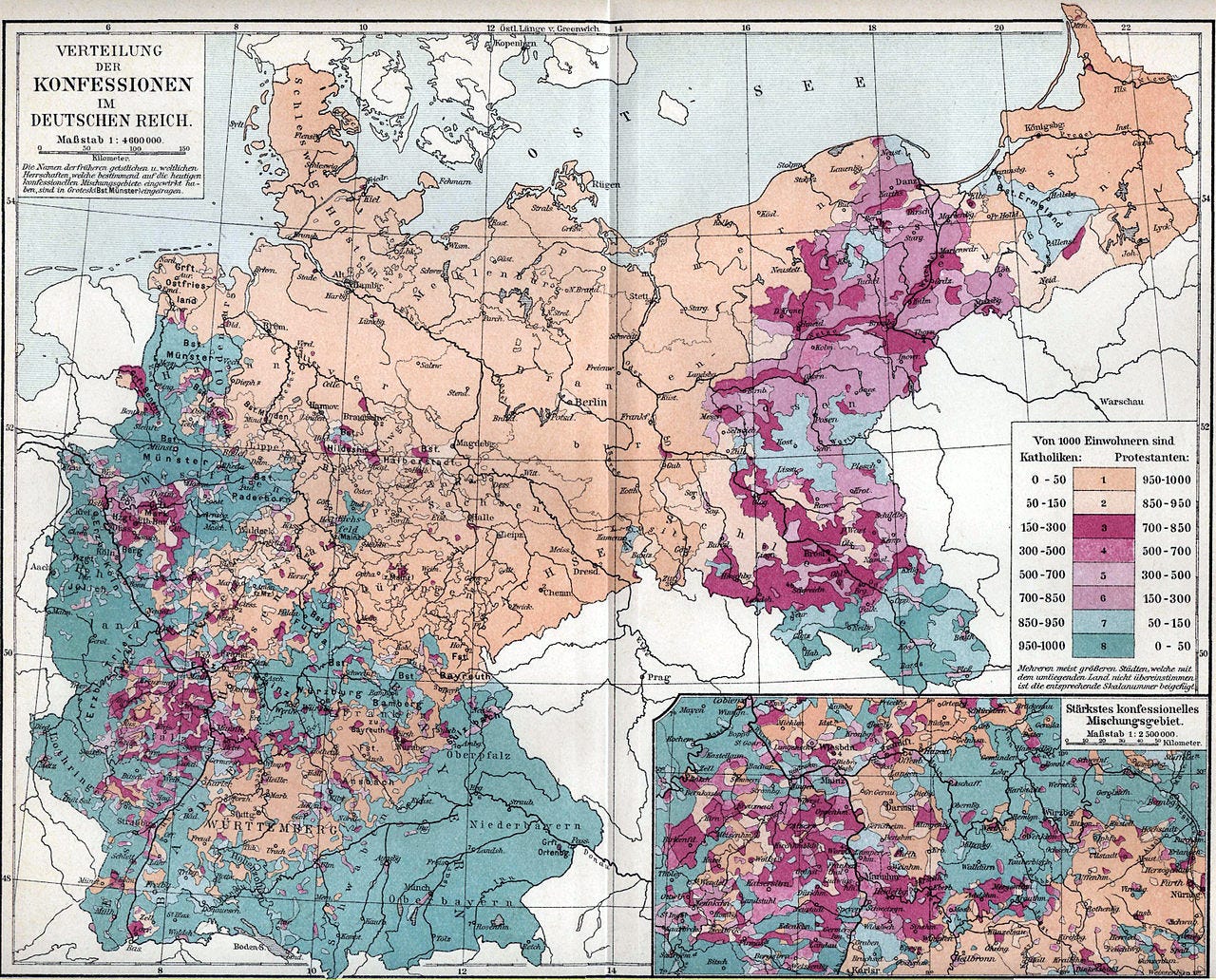

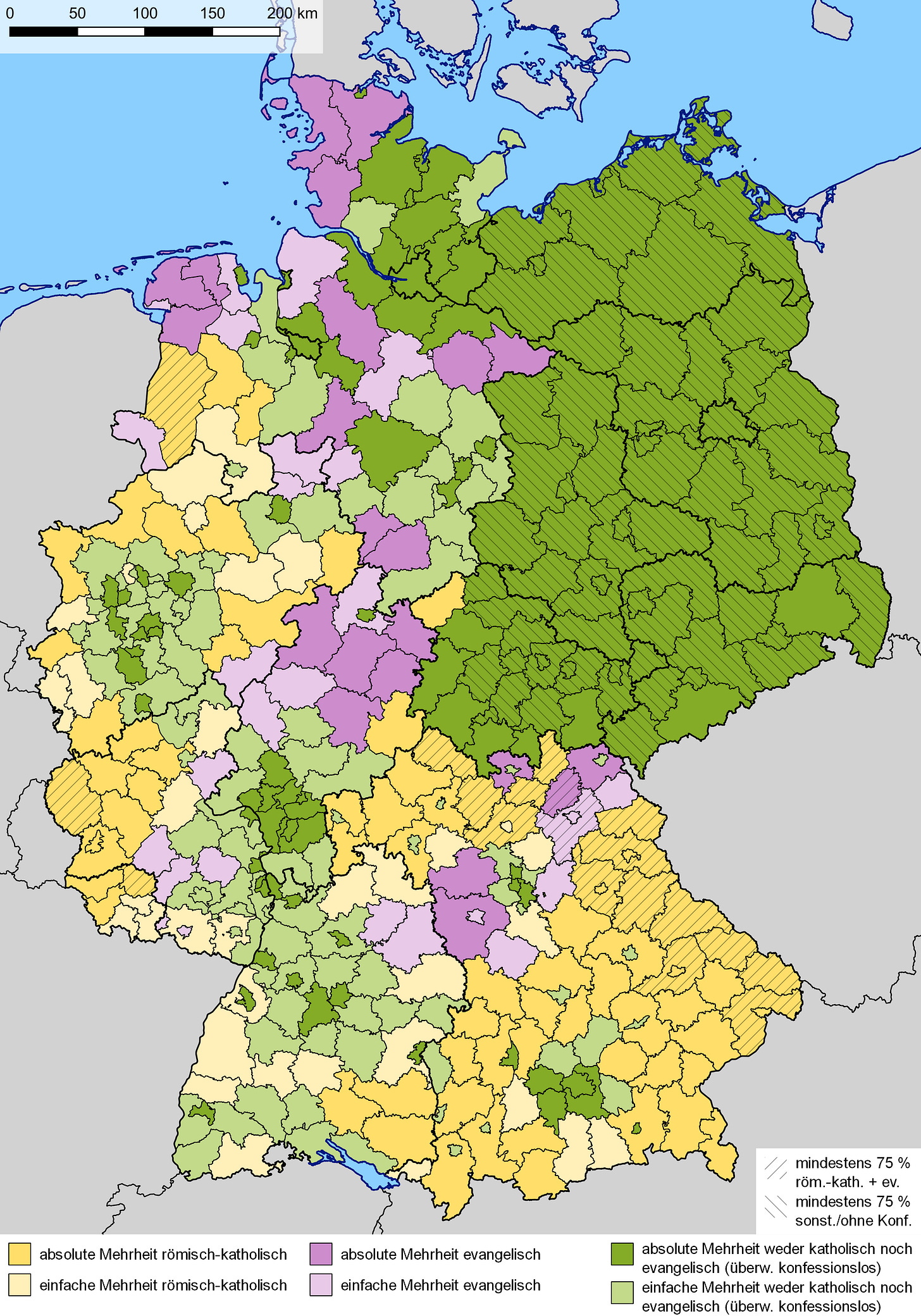

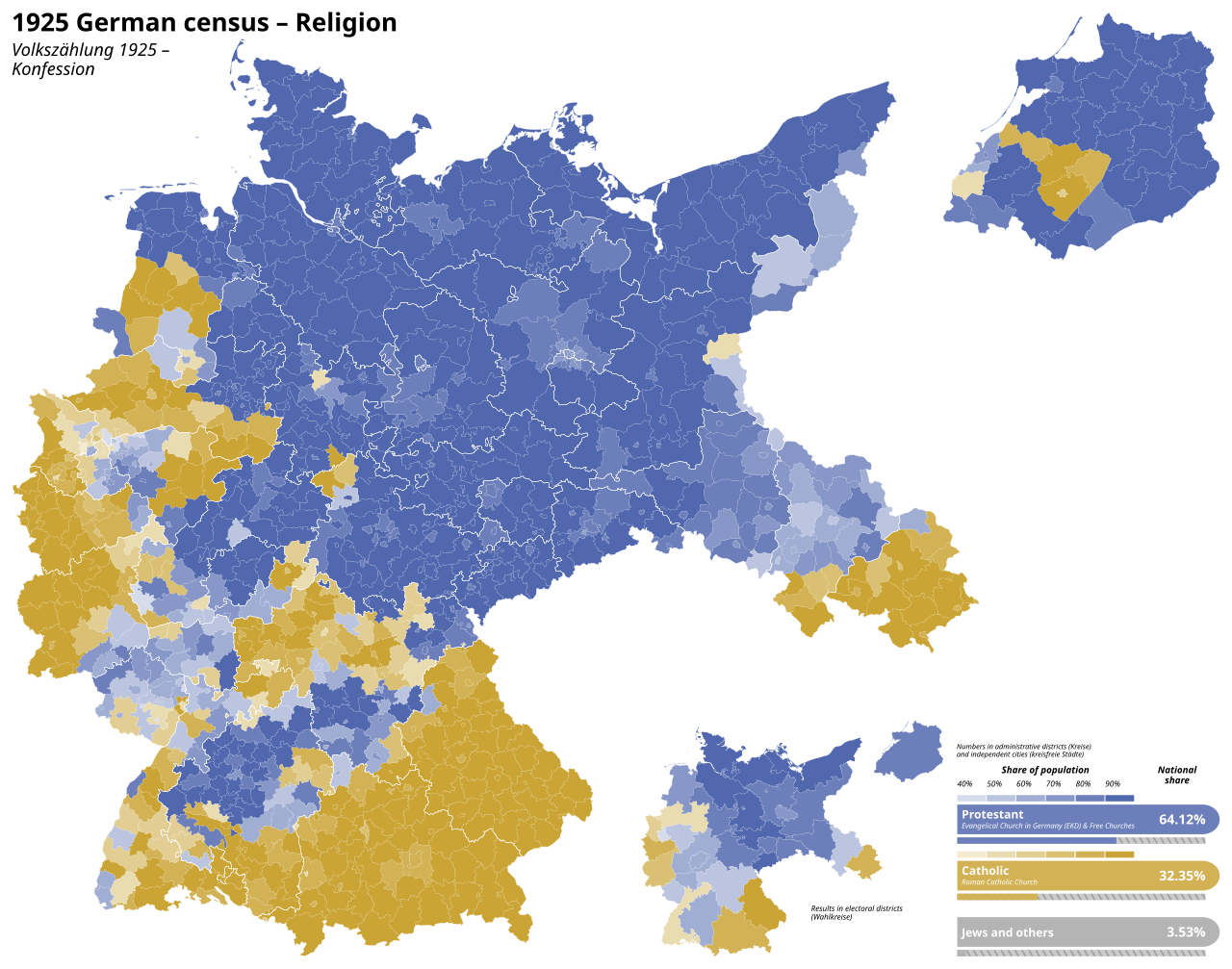

The conflict grew into violent political and military struggles, eventually leading to the Peace of Augsburg in 1555, which allowed each prince to choose the religion of his territory. Over time, these choices solidified, creating the broad north-Protestant and south-Catholic pattern that still shapes Germany’s religious landscape today. But because of the patchwork nature of this arrangement, there are pockets of Catholicism in Protestant areas and vice versa.

The exclusion of Catholic Austria from the German state founded in 1871 created a roughly one-third Catholic to two-thirds Protestant balance in the German Empire, which was now ruled by Protestant Hohenzollerns rather than the Catholic Habsburgs who had run the Holy Roman Empire. This had profound implications for the evolution of German nationhood.

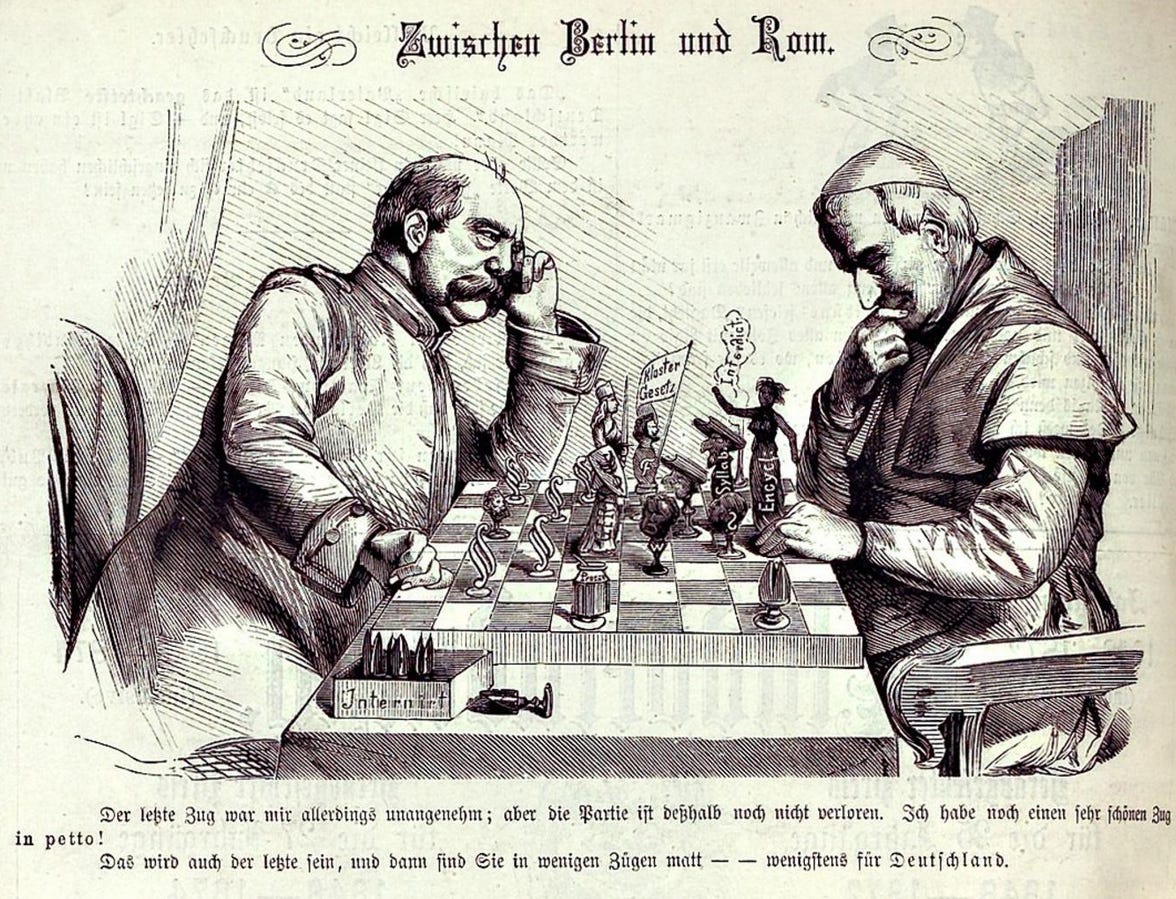

The first German chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, himself a Prussian Protestant, was deeply suspicious of Catholic political influence. In turn, the Pope saw the newly founded nation-states of Germany and Italy as projects hostile to the influence of Catholicism. Bismarck’s clash with the Pope over the hearts and minds of German Catholics went down in history as the Kulturkampf – Culture Wars.

Fast forward to the division of Germany after the Second World War. Suddenly, a large chunk of Protestant Germany was in the East, leaving West Germany with a far larger proportion of Catholic areas than previous versions of Germany – roughly a 50/50 split with a slight majority of Protestants – while the GDR began its political life with 81% Protestants and 14% Catholics. The latter’s systematic erosion of religion has turned eastern Germany into a majority-atheist society. As I discussed elsewhere, this is unique in the world, according to several studies.

What this religious fragmentation has done to German identity and social cohesion is very hard to isolate and define because of the many other layers of political, social, cultural and linguistic division.

Take the Thirty Years’ War, which derived from religious conflict in central Europe. It’s widely considered one of the most horrific and impactful wars in European, or even in human history. It can confidently be counted among the various traumatic experiences that contributed to the forging of a German identity. But it wasn’t just a religious conflict. It was also about power, social change and the emergence of a new era. What makes Bavaria different from Hamburg isn’t just religious differences but cultural, economic, social and historical factors, too.

However, religion is never just religion. It comes with cultural habits, rituals, social norms and, most importantly, a sense of belonging to a community. Take Christmas. You don’t have to be religious to consider this an important time in your year that comes with certain traditions, expectations and communal experiences like travelling “home”, meeting up with family, eating things you don’t for the rest of the year, etc. It’s something you have in common with people you have never met in your life. It’s part of a broader sense of a shared community. In Germany, a visible manifestation of this is the Christmas market tradition, which transcends class, denomination, regional differences and politics.

And yet, Christianity remains a tricky factor for German politicians today. Rightwing forces elsewhere — Chega in Portugal, Marine Le Pen in France, Tommy Robinson in Britain, Viktor Orbán in Hungary — have increasingly turned towards an emphasis on Christian values and tradition in their rhetoric and messaging, connecting this to national identity in a bid to create a sense of belonging for those who crave it.

The AfD can’t really do that in Germany. For one thing, much of the leadership of the Protestant and Catholic Churches is hostile to the party. But for another, it’s unlikely to work. While the AfD is growing in the West, its stronghold is still firmly in the East. An emphasis on religion would backfire. In the West, the landscape is divided between Catholic, Protestant and secular regions — not easy to navigate either without opening old wounds and religious tensions.

Since the end of the Second World War, German conservatives have sought to navigate this issue by building on shared Christian social values without emphasising differences between Catholicism and Protestantism. The Christian Democratic Union — the party of chancellors like Konrad Adenauer (Catholic), Ludwig Erhard (Protestant), Helmut Kohl (Catholic), Angela Merkel (Protestant) and Friedrich Merz (Catholic) — is a pan-denominational party that draws its conservative social values from Christianity as a whole.

The old dividing lines may be fading, but they still exist. I only recently heard Luther half-jokingly referred to as “that heretic” by a Bavarian commentator. Germany still has divided public holidays. Catholic states like Bavaria or North Rhine-Westphalia have All Saints’ Day, for instance, while Protestant ones, like the eastern states or Hamburg and Bremen, have Reformation Day. There used to be a radio prank programme where you could get the host to make an early-morning wake-up call to a friend in a state that had a public holiday when yours didn’t.

Yet there is a serious point here too: there is no cohesive religious identity in Germany beyond a shared Judeo-Christian cultural backdrop. For better or worse, religion is an awkward anchor for politics in Germany.

Now, I hope you will excuse me. Braga Cathedral beckons this East German atheist…

Thanks, very well writen account of that part of Germany. Another pecularity is Karneval, which has its roots in catholic tradition but dates back to the french occupation in Napoleonic times.

I do enjoy your trips to foreign lands and what you find there and linking it back to Germany. I was interested that you said how the AfD didn't use Christianity as part of its rallying call unlike similar far right groups elsewhere, I wonder if this makes them more or less attractive to voters having adopted this stance or is it something the average German east or West isn't bothered about.