German Women in Uniform

Will there be female conscription in Germany?

“Blimey, that’s massive,” a British friend texted this week, sending me a link to a news story about Germany’s military reforms. The coalition government in Berlin announced on Thursday that, after much wrangling, it had agreed on a plan to boost troop numbers from 182,000 to around 260,000 plus around 200,000 reservists — “the largest conventional army in Europe”, as Chancellor Friedrich Merz put it.

Since neither recruitment campaigns nor improved pay and conditions have shown any signs that Germany would get there with volunteers only, a partial conscription model is being reintroduced.

Under the new legislation, all 18-year-old men must complete a mandatory questionnaire assessing their health and willingness to serve. Then they will undergo medical screening from 2027. The government hopes this nudging and registering will produce enough volunteers. If not, compulsory service could be reinstated via a second law.

Legally, this is comparatively easy for the government to do because conscription is written into the constitution. Article 12A says: “Men who have attained the age of eighteen may be required to serve in the Armed Forces, in the Federal Border Police, or in a civil defence organisation.” In fact, conscription was only suspended in 2011. When we finished school, my male friends were still required to serve in the military or perform a civilian equivalent.

There was much grumbling on the boys’ side about the fact that women, myself included, were exempted. I looked on, half-amused, half-worried, as male friends did everything they could to get out of national service on grounds of being deemed medically unfit. Some ate a dozen eggs to mess up their urine samples. Others smoked cannabis to claim a dangerous drug dependency. Meanwhile, I filled out my university applications with complete planning security.

To make such a stark difference between men and women seemed very much at odds with society in the early 2000s. After all, nobody was actually forced into the Bundeswehr. The idea was more to do something communal for a few months. There wasn’t an obvious reason why such responsibilities should only fall to men.

Men could freely choose a civilian equivalent to military service so long as it was something deemed beneficial to others. I had friends who chose to work in homes for people with disabilities, in kindergartens or in forestry and landscape management. They were paid for it, too. So why was this not asked of women? Because it goes back to the post-war social order where society and the outside world were for men to shape while a woman’s domain was her family and the private sphere.

Society and norms had obviously changed by the early 2000s when we left school, but legislation was slow to catch up. It was only in 2001 that women gained access to all pathways of the Bundeswehr, and that wasn’t through legislation introduced by the centre-left government of the day, but through a ruling of the European Court of Justice. Joining the Bundeswehr has remained entirely voluntary for women. Currently, 24,000 women are serving. That’s about 13% of the total personnel.

The point of public service is a separate issue, I feel. If there is supposed to be complete parity between men and women in society, then that presupposes that both sexes share equal rights and responsibilities. In this day and age, you should either force everyone or no one to complete public service, in my view.

There are two hurdles to gender parity in this field. One is a legal obstacle. While male conscription already exists and only needs to be reactivated with a simple majority in parliament, female conscription is prohibited by the constitution. It explicitly states that women may only be “called up” during a “state of defence” and even then only when there are shortages “in the civilian health system or in stationary military hospitals”. The last sentence reads: “Under no circumstances may they be required to render service involving the use of arms.”

So while Merz and many others think there should be gender parity in national service, they would have to change the constitution to get there. That requires a two-thirds majority in parliament, and that is currently hard to come by on any given issue.

The left-wing party Die Linke, for instance, is uniformly (no pun intended) opposed. Desirée Becker, their spokesperson for “peace and disarmament” said that national service would amount to “robbing women of a further year of independent life” which “has nothing to do with real efforts for equality”. Currently, the government is tiptoeing around the issue, sending women the same questionnaire as men but leaving it optional for them to return it.

The second big hurdle is a social one. There can be no doubt that society has changed as regards gender roles. Germany had a female chancellor for sixteen years. Three-quarters of women of working age are in employment. In the 1950s, when the above articles were anchored in the constitution, only 31% of West German women worked. Nonetheless, as the significant gender disparity in the volunteer-based Bundeswehr shows, committing to military service is still not a thought that comes naturally to many women.

In East Germany, many more women worked than in West Germany or any other country, for that matter. But the regime also found out that this didn’t mean women were necessarily keen to do military service. In contrast to West Germany, it allowed women to serve, including in officer roles from 1984. Yet, despite being a dictatorship, it never quite dared force them to either.

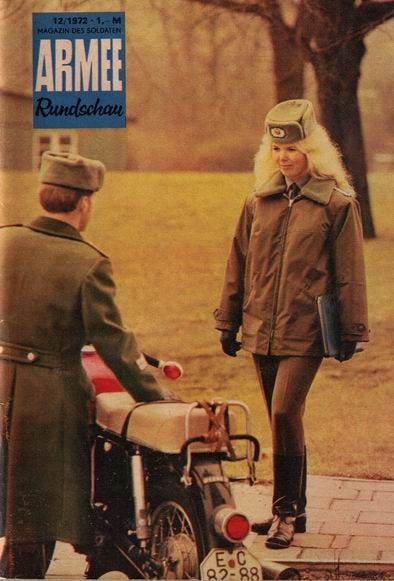

While it did require women and girls to undergo civil defence training, it didn’t compel them to complete military service, as it did for men. Even when, in 1982, a new law decreed that women could be drafted in case of an attack, protest groups formed. So the authorities tried a different strategy: to entice more female citizens into their armed forces with adverts and an image campaign showing women in uniform and in various training scenarios.

Some loved the idea because they were bored with their jobs, and there were few opportunities to change what you did once you were in a certain sector. Kerstin Haack, whom I interviewed for Beyond the Wall, is an example. She joined the air force, initially being the only woman in her unit. But there wasn’t the take-up the government had hoped for. In 1989, the GDR had 170,000 soldiers; only 2,000 were women. The state had planned for 3,500.

Of course, 36 years have passed since then, and German society has changed. The Bundeswehr has also tried to make its pathways attractive to women by supporting career opportunities like university courses. But conscription is a different matter.

Some recent polling suggests that while a majority of Germans are for the reintroduction, the picture is less positive when it comes to female subscription. While 55% of men said they’d want it applied to both sexes, only a third of women agreed. That indicates that drafting women might be met with some protest and resistance.

Either way, the government has decided to opt for a voluntary course for now. I sincerely doubt we’ll see a considerable increase in German women in uniform any time soon. I’ll leave it up to you to decide whether that’s a good or a bad thing.

I enjoyed that. I had forgotten that the requirement for young men to do military or civilian service had been suspended. I do remember lots of the young men I knew in the 70s going to interesting lengths to avoid conscription, including in some cases extending their university studies for several years, taking years abroad, etc. A number of people also moved to West Berlin, where you were exempt from service. I would imagine there may well be lots of opposition among young people to moves to reinstate it, especially for women. It will be interesting to see what happens.