Germany's title dealer is dead

The country's love of titles is not

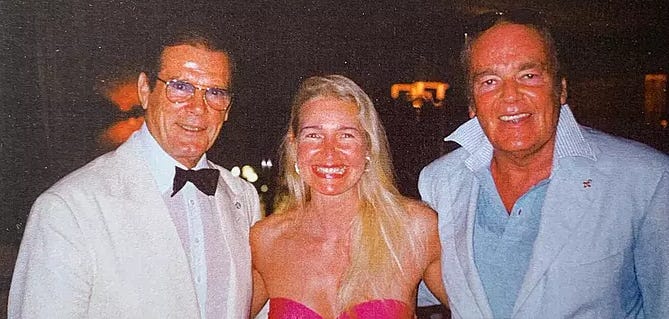

My phone rang last week when I was in the middle of something. Absentmindedly, I picked up. It was a show editor from Times Radio: ‘You know, Hans-Hermann Weyer died. Would you be able to come on the radio next week to talk about him?’ My first thought was: who died? But then it came to me. Yes, of course: ‘Consul Weyer’, also known as the ‘handsome consul’ or ‘Consul Weyer Graf von Yorck’, as he styled himself – a colourful character who used to fill the gossip pages with stories of stupendous wealth, a jetset lifestyle, fraud and politics.

Seen by many in Germany as a harmless rogue, a celebrity figure who lived a life some envied him for and others found outrageous, he was seemingly important enough to warrant an obituary in The Times. But the paper is right, of course, Weyer’s story is interesting beyond the gossip. It reveals a lot about the insecurities of the new elites West Germany produced after the Second World War.

Weyer made his money trading in titles and honorific positions. Want a bit more respect from society than is normally bestowed on successful used car salesmen? Become the honorary consul of a minor South American country that can’t afford a real one. Feel ‘sausage factory owner’ doesn’t quite cut it at the dinner parties you have been attending since you’ve accumulated a respectable amount of wealth? Acquire some professional dignity with a doctorate from the fictional Sheffield Philosophical University. Next time, when your host introduces you as Dr Schmidt, nobody will think a crude joke is the appropriate response. Weyer became the man who made it possible for West Germany’s nouveau riche to acquire the facade of the social and professional status they so desired.

Weyer and his bizarre but successful business idea were a product of his time. Nazism and the Second World War had bankrupted Germany in every way: politically, economically, socially and morally. The way to deal with this and build back was to call 1945 modern Germany’s Stunde Null - Zero Hour. At that moment, a new country would be born out of the ashes of the old. Gone were the militarism, injured pride and social hierarchies of old. In came pacifism, prosperity and social mobility. But reality did not quite live up to this platonic ideal. People don’t just give up their mentality, outlook and insecurities because history decides it’s time for a new marker on the timeline.

The German middle classes had felt extremely conscious of their lack of titles and illustrious family trees for decades. In the second half of the 19th century, they had pushed for German unification under a constitutional framework that would afford them equal rights in front of the law and political power through elected offices and democratic votes.

But even the Weimar Republic, which replaced Germany’s constitutional monarchy in 1918/19 with an ultra-democratic system run by many politicians from the lower middle classes, didn’t manage to replace the old elites in areas such as the judiciary and the military. What the middle classes had to shield themselves from a sneering Count or the biting comments of a Duchess at dinner parties was professional pride and position.

Even the Nazi elite was painfully conscious of this. Joseph Goebbels signed all his documents as Dr. Goebbels. Hermann Göring even had a military rank invented for him, that of Reichsmarschall which sat at the top of Wehrmacht hierarchy, above all the officers with noble titles.

After the war, this system of reference was nominally binned with the rest of Germany’s dysfunctional social norms. But in reality, the middle classes still often felt they had nothing to show for their successes but money. The ‘economic miracle’ years of West Germany’s 1950s had allowed many to acquire enormous wealth and influence but money couldn’t always buy them confidence. And this is where Hans-Hermann Weyer stepped in.

The son of a Luftwaffe officer, Weyer was born in 1938. He claimed in a press conference in 1981 that he was not just named after Hermann Göring but that the Reichmarschall had been his father’s close friend and his own godfather. Given that Weyer made a very successful career of outrageous claims and pretences, this is to be taken with a pinch of salt. But it is definitely possible that his father admired Göring for his successes as a fighter pilot in the First World War and for his position as Chief of the Luftwaffe High Command.

But the war did not go well for Weyer’s father. He was captured by the Red Army and held as a prisoner of war in the Soviet Union until 1955, when the West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer negotiated a mass release of the remaining German POWs. But that was ten years after the end of the war. When he was released and returned home to Berlin, Weyer Senior found that his wife had already declared him dead and remarried. Weyer Junior was raised by his stepfather, a British officer called Clifford Davis.

Weyer claims that it was through his illustrious stepfather that he made his first contacts in the world of diplomacy. As a young man, he travelled to Uruguay to find his biological father who had gone underground in South America. He also made the acquaintance of several diplomats and dictators from countries who had neither the money nor the inclination to run proper embassies and consulates in all European countries. But they were happy enough to accept money to make someone a consul. Weyer as the middle man would receive half the money. In 1978, he claimed he had sold 80 consular titles – saving one for himself. Weyer now styled himself the Bolivian consul in Luxembourg.

Aristocratic titles were another favourite of Weyer’s wealthy but insecure clientele. He cleverly exploited both Europe’s impoverished aristocracy and the continent’s newly risen stars who felt they lacked pedigree. The solution was simple: bring money and status together. For a certain price, Weyer would match the new economic barons with impoverished aristocrats who would either marry or adopt them and thereby bestow their titles on them. Weyer once again took advantage of his own scheme. The Countess of Yorck adopted him in 1996, allowing Weyer to introduce himself as Consul Weyer Graf von Yorck.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to ZEITGEIST to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.