Germany has never had its own nuclear weapons. Even now that it intends to rearm on a massive scale, the new government is keen to stress that it wants to build the ‘largest conventional army in Europe’.

The absence of nuclear weapons from rearmament has to be stressed because Germany has the means, the material and the knowledge to develop nuclear weapons but has agreed not to do so under two post-war treaties.

Under the radar, a debate is brewing as to whether Germany should develop its own nuclear weapons. German scientists were at the forefront of developing nuclear weapons in the first place. Yet, this scientific history is deeply intertwined with Germany’s Nazi past and the Second World War.

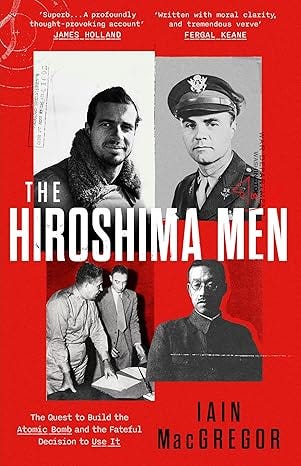

So this Sunday, let’s go back and have a look at Germany’s first attempts at building nuclear weapons with this guest piece by my fellow historian, Iain MacGregor, most recently the author of the highly recommended The Hiroshima Men: The Quest to Build the Atomic Bomb, and the Fateful Decision to Use It.

How Fears of a Nazi Atom Bomb Fuelled the Manhattan Project

By Iain MacGregor, FRHistS

In the years leading up to the Nazis' rise to power in 1933, Germany had been a leader in many fields of science, with its universities conducting pioneering studies in both chemistry and physics during the first decades of the twentieth century.

Germany led the international table for the most Nobel Prize winners in the sciences, including Albert Einstein and Werner Karl Heisenberg. Both men would play a significant part in the rapid advancement of the weaponisation of nuclear technology for different reasons.

As war loomed once again in Europe, and tensions rose between the United States and Imperial Japan in the Pacific, the fear of the long-range bomber delivering lethal payloads of ordnance dominated governments’ thinking. In Europe and in the United States, leading scientists began to have their work analysed and accepted, should they offer one side or the other a super weapon.

The discovery of nuclear fission by scientists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann in 1938, followed by its theoretical explanation by Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch, made creating an atomic bomb theoretically feasible.

Their breakthrough experiments had revealed that uranium atoms could be split to release enormous amounts of energy, far more powerful than any conventional ordnance then being used. The discovery ignited a global enthusiasm for developing nuclear energy and, potentially, nuclear weapons – not least in Berlin.

As war in Europe became a very real threat, concerns grew that Nazi Germany might develop such a weapon first, especially among those scientists fleeing fascist regimes and bringing their fears to the governments of Britain and the United States.

The foundations of Germany's nuclear program were laid in 1939. The Germans quickly initiated a research effort under the auspices of the military, with physicists such as Werner Heisenberg and Kurt Diebner leading investigations into nuclear fission, isotope separation, and reactor design. Their early work showed that achieving a sustained chain reaction was possible and that materials such as uranium-235 and plutonium could function as explosive fuels.

That summer, a few days before Hitler invaded Poland to spark a new European war, Hungarian physicists Leo Szilard and Eugene Wigner drafted the ‘Einstein–Szilard’ letter, warning the President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, about the potential for powerful, new bombs and urging the U.S. to accelerate uranium research.

With a signatory of the stature of Albert Einstein attached to it, it spurred Roosevelt’s government into action, establishing at first the Advisory Committee on Uranium, which later became part of the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC).

Even with the successes of Hitler’s armies across Western Europe in the summer of 1940, the budget Roosevelt’s administration set aside was limited – a twelve-man committee allocated just $600,000. Still neutral, the country did not yet have the industrial or economic power to offer more.

Meanwhile, Britain had independently made advances, with its own team of German-Jewish scientists who had escaped Germany, Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls, issuing their memorandum, which concluded that a small amount of enriched uranium-235 could produce a powerful bomb. It kick-started the British atomic bomb effort, which then offered to share its research with the Americans.

Through collaboration and information exchange, American scientists became more aware of the potential of nuclear weapons. By June 1941, prior to Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union, Roosevelt signed an executive order establishing the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD). This body would galvanise America’s civilian technological and scientific base to work alongside the United States armed forces in order to rebuild the country’s military strength.

By early 1942, with America now fighting a war on two fronts with Germany and Japan, the race for nuclear technology was paramount, as Roosevelt’s advisers feared Hitler’s scientists were at least a year ahead of them. Money was now no barrier, only time was ticking.

The OSRD established the U.S. Army’s secret nuclear weapons programme – the Manhattan Project, led by General Leslie Groves, and Professor J. Robert Oppenheimer. The top-secret project would employ over 130,000 people in factories, science laboratories, test sites, reactors and countless military bases right across the country. The majority of whom had little idea what their work was creating.

But, what of the fear of a Nazi atom bomb? Well, it was never really a threat. While the Germans still had many gifted scientists willing to serve the regime, and made significant strides in nuclear research, Germany would ultimately fall far short of developing an atomic bomb comparable to those dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. Several factors, including leadership decisions, resource limitations, scientific focus, and strategic priorities, contributed to this outcome.

Despite their scientific advances, Nazi Germany’s progress toward weaponisation was hampered by practical and strategic decisions – systemic failures that were repeated in many areas of government as well as military campaigns.

Unlike the overarching commitment seen in the American Manhattan Project, the German effort lacked full-scale industrial backing. The German leadership delegated by Hitler to oversee it: the gaff-prone Hermann Goering constantly worked against his more gifted Nazi administrator, Albert Speer as both men fought for the Fuhrer’s attention.

In their wisdom - or perhaps shortsightedness – both Nazi ministers prioritised conventional military hardware like rockets and jet aircraft over nuclear weapons. With a limited budget, a science team weakened by other projects or being called up to fight, and a faltering Russian campaign, as the war dragged on, the physicists they did have focused on research into plutonium and uranium, rather than its mass production.

The decision to use heavy water from Norway as a moderator further slowed progress, especially when Norwegian resistance commandos destroyed large sections of their heavy water supplies. Ultimately, therefore, limited resources and the inability to produce enough enriched uranium or plutonium prevented the Germans from scaling up their experiments to produce a functional bomb.

By the war’s end, as the Manhattan Project was on the cusp of realising an atomic bomb, the Germans had managed to build reactor prototypes nearing criticality but had not succeeded in weaponising their research.

In the last stages, a clandestine test of a small device hinted at possible nuclear reactions occurring, but whether this resulted in a true nuclear explosion remains uncertain. The fact that they could not mobilise their scientific efforts into a wartime weapon of comparable destructive power to the Allied bombs underscores a critical gap: the Germans lacked the political will and strategic focus necessary to transform scientific achievement into effective military technology.

The Germans believed that nuclear weapons were scientifically feasible but not imminent or essential to winning the war, especially after key victories in Europe early on gave them supremacy across large swathes of Europe.

They believed, as Imperial Japan did with their rapid success in the Pacific in 1942, that they were invulnerable to that sort of attack. As the tide of war turned, the focus of Hitler’s regime shifted to one of survival using conventional military muscle. Valuable time, effort and money for nuclear research would become a secondary priority. By the time their nuclear program gained momentum, it was too late to produce a weapon of comparable power.

Nazi Germany’s nuclear ambitions would ultimately be thwarted by a combination of strategic neglect, resource constraints, and changing wartime priorities. Although Hitler’s regime possessed the scientific knowledge and some of the necessary materials, it never fully committed to developing nuclear weapons as the Americans did.

The result was a scientific effort that remained on the cusp of achieving a weapon but ultimately failed to realise the destructive potential of nuclear armament, illustrating how leadership choices and strategic focus can determine the outcome of technological endeavours in wartime. The major irony being, by the time Soviet tanks were crashing through Berlin in May 1945, Hitler’s V1 and V2 rocket programmes had drained resources in men and materiel on a level similar to the Manhattan Project.

Iain MacGregor is a fellow of the Royal Historical Society and author of the recently published The Hiroshima Men: The Quest to Build the Atomic Bomb, and the Fateful Decision to Use It.

Nice one Iain 👍 I have the book this will encourage me to read it soon and it features in the upside down book club

Thanks Iain. I’m looking forward to reading your book, I’m picking up a copy at an event in Toppings, Edinburgh. I wonder if we would have used the bomb in Germany? Perhaps it would have been difficult to find a suitable target given the destruction wrought upon Germany by July ‘45. I recently read Tooze’s The Wages of Destruction and a few years ago I read a book about the Manhattan Project; as you say Nazi Germany lacked the resources. A couple of weeks ago I listened to an episode of In Our Time about Lise Meitner, all new to me. Good read with my Sunday morning coffee.