Inside the Stasi HQ

Where past and present converge

I am sitting in the Members’ Room of the British Museum in London, sipping cold Rose Lemonade from a glass bottle as I’m trying and failing to write this piece. I start and stop and start again. In this most British place, it’s difficult to capture the atmosphere of my visit to Berlin. It smells of cake. A coffee machine hisses in the background. A middle-aged couple glumbles about a bunch of primary school children in high-vis vests ruining the atmosphere in the galleries.

It’s hard to believe I had a potato salad and frankfurters in Berlin just a few hours ago. Now, I’m looking through a large bay window to my left into the light-flooded Great Court of the British Museum where yellow-clad mini-tourists are pleading with their teachers to be allowed into the gift shop. I feel strangely detached from it all – one of those side effects from crossing between countries and cultures too quickly. But there was one connection: Karl Marx.

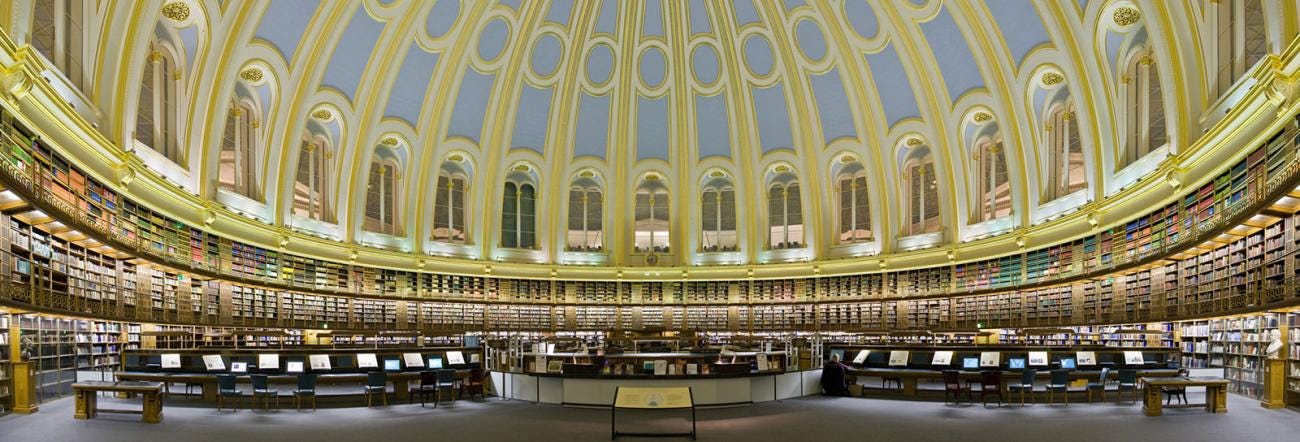

Lifting my gaze up from the bustling chaos on the ground to the middle of the Great Court, I’m looking at the back wall of the huge round Reading Room. It’s impressive now, but when it was first opened in 1857, it must have been truly mind-blowing: built with materials like glass and concrete and sporting the latest heating technology, it was ultra-modern in its day. Three miles of bookcases and 25 miles of shelves contained an awe-inspiring amount of words and knowledge.

When the Reading Room was briefly opened to the public for eight days to view, 62,000 came. But ultimately the Principal Librarian was the arbiter of the desirable reader’s tickets. Karl Marx, who had been expelled from his German homelands and settled in London in 1849, held one of them. Now, 175 years later, another German (albeit one in voluntary exile) is seeking inspiration here.

Marx also looked over my shoulder in Berlin the previous evening. Quite literally. There is a statue of him in the foyer of the former headquarters of the Stasi, the infamous state security agency of East Germany.

I and two other panellists had been invited there to talk on the anniversary of its storming by protesters on 15 January 1990. This event took place just a couple of months after the Berlin Wall had fallen and the building had been the workplace of the Stasi’s ruthless chief Erich Mielke and his staff. The protesters and others decided that it would become a “Memorial and Research Centre of GDR Stalinism.

Today, the chillingly mundane office building complex is a strange hybrid: a museum space with neat exhibitions about the Stasi and a slice of East German history frozen in time. And so there we were: three generations of historians talking to an audience that included people who had burst through those doors to our right 34 years earlier while busts of Karl Marx and Felix Dzerzhinsky (Soviet police chief) flanked our panel.

Both statues are small copies of Russian monuments. That of ‘Iron Felix’ had once dominated the square then named after him in front of the KGB headquarters in Moscow. It was removed when the Soviet Empire fell and reerected last year in front of the headquarters of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service. Karl Marx, casually leaning on a podium carrying the motto of the Soviet Union: “Пролетарии всех стран, соединяйтесь!” – "Proletarians of All Countries, Unite!" still stands near the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, protected as a historical monument by law. The present and the past are fluid in Moscow as they were at the Stasi museum on Monday night.

The director casually asked me if I could read the Russian slogan on Marx’s plinth. I could, but only with painful clumsiness — my Cyrillic skills are a little rusty. The same was probably true for most people in the room. As people born in East Germany, we’d all learnt Russian at school. That applied to me even though I went to school when the country that had trained my teachers no longer existed.

There was nervous banter as microphones were carefully tucked behind ears. “You may talk freely. They aren’t switched on yet,” the sound technician reassured us. “And I’m sure that sentence has never been said in this place before,” someone joked. It was hard to escape the fact that Mielke’s former rooms were right above us, preserved in aspic.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to ZEITGEIST to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.