Living with the Past: Julia Franck’s Worlds Apart

A Review

I’m out and about in London today, excited to meet one of Germany’s most celebrated contemporary authors: Julia Franck. Her books have been translated into over 40 languages. Her most successful novel, Die Mittagsfrau (The Blind Side of the Heart), won the German Book Prize, was adapted into a film and has sold over a million copies worldwide.

But I’m in London to talk to her about a story that’s even stranger than fiction: her own. In her latest book Welten auseinander (Worlds Apart) she recounts her life growing up in a fractured family that straddled the fault lines of German division. It’s one of the most bizarre life stories I have ever come across, but also one that’s remarkably closely intertwined with the strands of German history.

Worlds Apart is one of those books that involves you both intellectually and emotionally. On the surface, it is an autobiographical account of the author’s first 23 years, from her birth in East Berlin in 1970 to her early adulthood in the years surrounding German reunification. Yet very quickly it becomes clear that this is not simply a personal memoir. Franck’s story, fractured and often unsettling, mirrors the emotional and psychological mess of Germany’s twentieth century in striking and revealing ways.

Franck grows up in a family defined by instability. Her mother is an actress who struggles to care for her children both emotionally and financially. Her absence as a carer leaves lasting marks. The father is largely missing. When Franck is eight, her mother decides to leave East Germany, taking her children across the border to the West. This decisive moment might suggest escape or freedom, but Franck tells a much more complicated story. The move initiates a new phase of dislocation in a long line of such family events.

After passing through the refugee centre at Marienfelde – itself a highly unpleasant experience that lasted months – the family is sent to a decaying farmhouse in Schleswig-Holstein in the far north of West Germany. Life there is defined by poverty, cold and neglect. Franck describes living on state welfare with a chaotic and impulsive mother as a sequence of endless domestic labour, hunger and a lack of adult supervision. Yet she does so with an unsettling calm. There is never any self-pity or anger in her narrative voice.

She and her sisters learn early to rely on themselves. What makes these scenes so powerful is the absence of overt commentary. Franck trusts detail to carry meaning, allowing readers to grasp the emotional consequences without being guided toward a particular response.

As the book unfolds, it becomes clear that this story cannot be understood without looking further back and without breaking chronology. Welten auseinander is deeply concerned with inheritance, not only genetic and emotional but also historical.

Franck’s grandmother Inge Hunzinger was a sculptor and a committed – if complicated – communist whose life spanned the Weimar Republic, National Socialism, postwar reconstruction and the realities of cultural life in East Germany. Her great-grandmother Lotte was Jewish and survived the Holocaust. These lives form a kind of submerged architecture beneath Franck’s own experiences. The words “intergenerational trauma” sprang to mind, but I’m not sure that they are right. It’s just one item on a long list of questions I have prepared to put to Franck when I see her later.

Remarkably, Franck never passes judgment on any of her relatives’ actions or their inaction. She merely recounts their remarkable lives as the backdrop to her own. The political convictions, silences and emotional wounds of earlier generations echo through the household she grows up in. Her mother’s fragility makes more sense in this light, yet it’s always clear that she – like everyone else – has a chance to break out of the circumstances she was thrown into. But Franck’s story also suggests that the traumas of the twentieth century did not end in 1945 or 1989. They linger, often invisibly, shaping family dynamics and inner lives to this day.

The divide between East and West Germany is another recurring thread. After leaving the East, Franck never quite belongs in the West. She is marked by difference, by accent and by experience. Later, when she moves to West Berlin as a teenager and begins living independently at the remarkably tender age of thirteen, the city offers both possibility and precarity. She works while attending school, navigating adult responsibilities while still a child. Freedom, in her account, is inseparable from risk.

Reunification is told less as a political spectacle than as a personal event with immediate consequences for her life and her family. The collapse of borders does not magically repair broken relationships or resolve long-standing emotional damage. Instead, it adds another layer of complexity to unstable identities.

Stylistically, Welten auseinander is very interesting. The language is plain, simple and immediate. It reads less like a traditional autobiography and more like a carefully composed literary work. Franck moves back and forth in time, sometimes writing from within childhood experience and sometimes observing her younger self from a reflective distance, switching between first and third person. This shifting perspective gives the book its rhythm and emotional depth. It’s almost a little stream-of-consciousness at times, but without ever losing its clarity.

Memory here is deliberately presented as not orderly or complete, but selective and charged, shaped by what continues to demand attention or by the themes the author wants to explore. Franck reflects on the peculiar way we recollect things explicitly, musing, for instance, that growing up with a twin sister has had a huge impact on how she remembers her own childhood.

Despite its difficult subject matter, the book is not without warmth or lightness. Franck allows moments of humour, curiosity and desire to surface. At times, I laughed out loud, such as when she describes herself and her twin getting up to no good, adding that the sisters, of course, sometimes have qualms about their misdeeds – just rarely at the same time.

Her search for her biological father, his brief reappearance in her life and his early death are described with emotional clarity rather than melodrama. But they still resonated with me because I watched my own father die a couple of years ago, and the scenes in Franck’s book brought back those memories.

I gather from interviews she gave that other readers responded very strongly to her descriptions of her first romantic relationships, which are portrayed as formative and painful, offering connection while also exposing vulnerability. These moments signal the gradual emergence of a young woman beginning to claim agency over her life.

German reviewers have praised Franck’s restraint and precision, noting her refusal to offer easy explanations or consolations. I’d go with that. She does not frame survival as triumph, nor does she seek redemption through narrative closure. Instead, she presents a life shaped by damage and endurance, insisting that both can coexist.

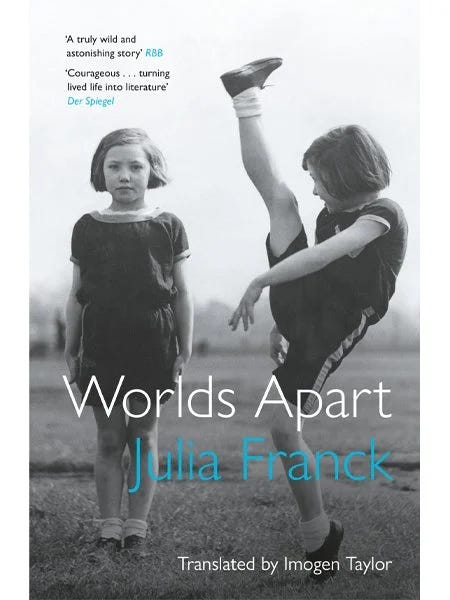

The English version, Worlds Apart, translated by Imogen Taylor and published in the United Kingdom by Moth Books this month, opens this work and the world the author grew up in to a wider readership. Franck’s prose, measured and exact, lends itself well to translation – though there are huge challenges with colloquialisms and language peculiar to Franck and her family. But the book’s themes of family, inheritence and the reverberating impact of history on individuals will resonate far beyond a German context.

Ultimately, Worlds Apart is compelling because it shows how a single life can illuminate a broader historical reality. Franck’s story is unusual, even wild and extreme, yet it feels recognisable in its exploration of trauma, displacement and the search for belonging. In tracing the fault lines of her own past, she reveals how deeply personal lives remain entangled with history long after the events themselves have passed.

I am looking forward to discussing this book with Julia Franck and her translator Imogen Taylor tonight at the Goethe-Institut in London, where I’ve been invited to host the UK launch. For more information or if you happen to be in town and want to come along, please visit the Institut’s website. More information about the book can be found here.