Man and Myth: Konrad Adenauer at 150

Or: "Westalgie" - Why nostalgia for West Germany is growing

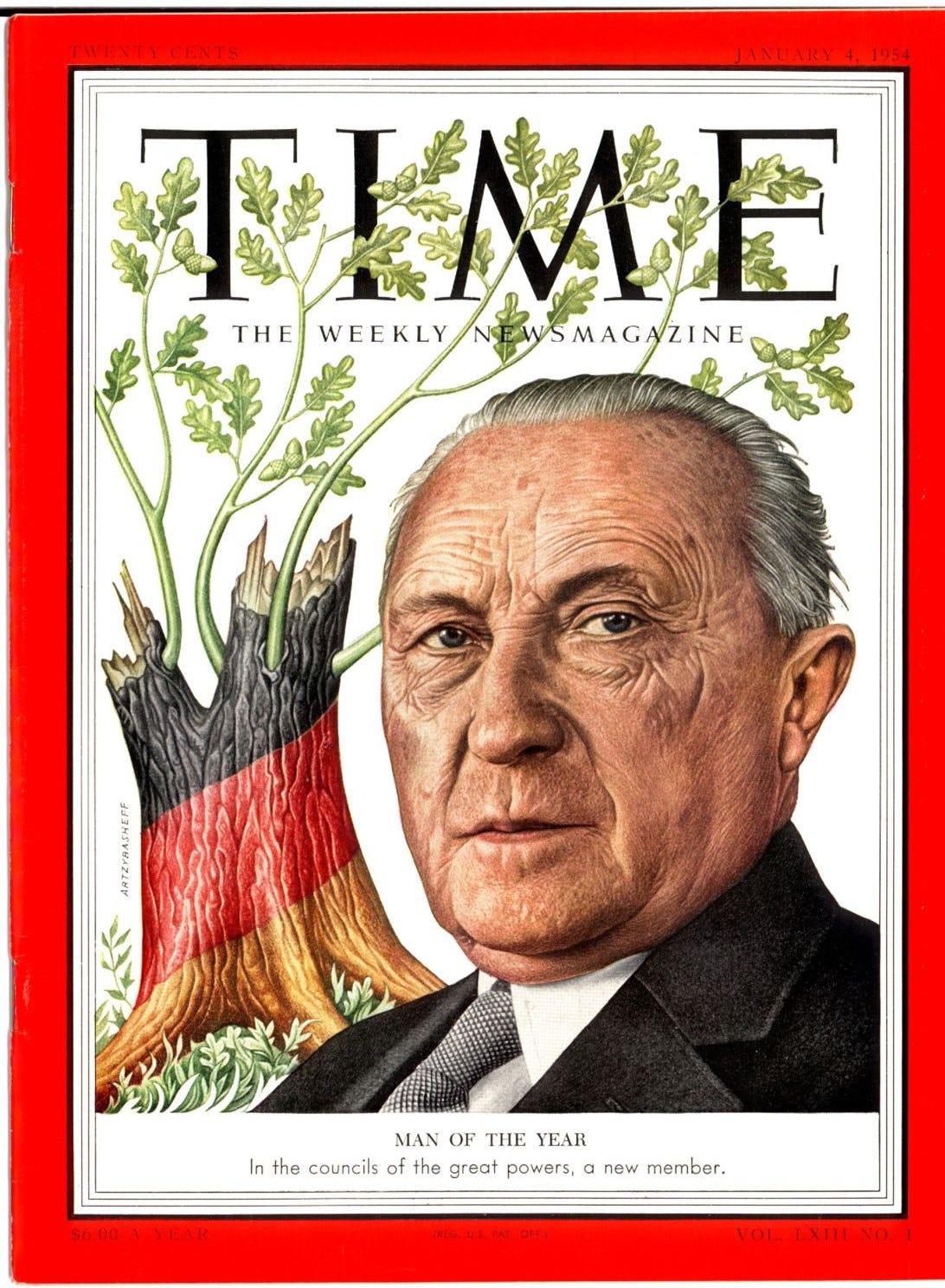

Konrad Adenauer was already known as “der Alte” or “the Old Man” during his lifetime. When (West) Germany’s first post-war Chancellor died in 1967 at the age of 91, he was still a member of parliament, setting an age record for active MPs that still stands today.

Had Adenauer lived much longer still, he would have celebrated his 150th birthday this week. But even without his presence, he was widely celebrated – particularly enthusiastically by a West German-dominated media landscape that is increasingly looking back to the post-war decades through the soft filter of nostalgia. “Ostalgie”, nostalgia for the former East Germany, is often a reproach former citizens of the GDR get to hear when they talk about their own past. But there is “Westalgie”, too, and that’s got a lot to do with the times we live in today.

Don’t get me wrong. As a historian, I have great respect for Adenauer. The first Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany set the course for Germany’s immensely successful political, economic, and moral reconstruction after the Second World War and Nazism, and in doing so, he had to overcome enormous challenges.

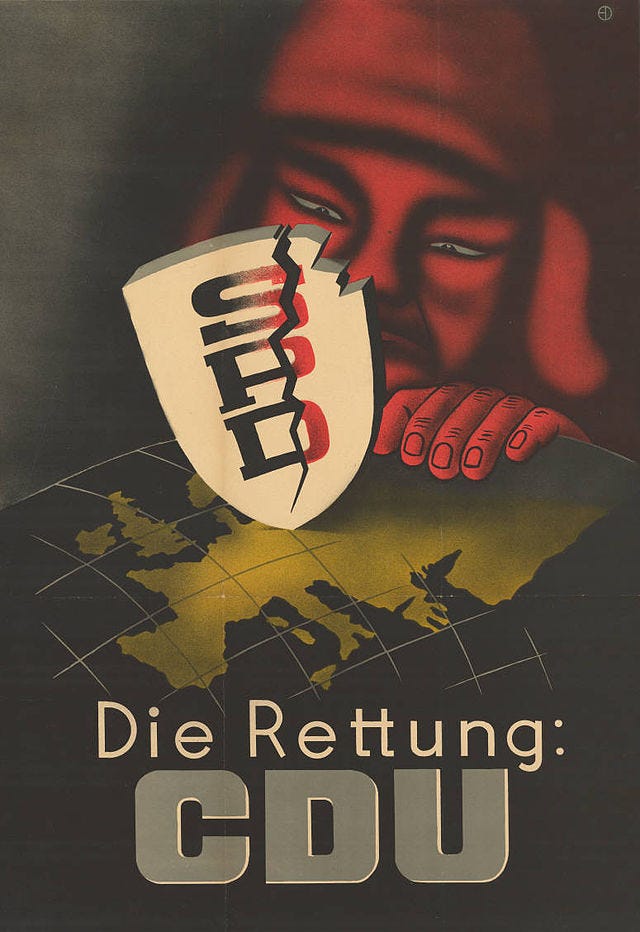

Initially elected to office in 1949 by a narrow margin – famously by just one vote, his own, as people joked at the time – he soon won over most West Germans to his policies. In the 1957 election, the CDU/CSU, under his leadership, achieved the only absolute majority (50.2%) in post-war German history and could have governed alone. Without a doubt, Adenauer accomplished a great deal and built a social consensus that is unimaginable today.

Given the highly polarised political landscape in today’s Germany, where many yearn for greater cohesion and governmental competence, I can understand why the seemingly idyllic world of post-war West Germany becomes a place of longing, and why a more nuanced approach – obligatory in all other aspects of German history – causes unease. However, this nostalgia for the old West, understandable as it may be on a human level, threatens to drift further and further away from the complexities of historical reality.

This week, Adenauer received almost exclusively effusive praise. German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier lauded him as a “great democrat” whose actions had been vindicated by history. The Süddeutsche Zeitung ‘s eulogy was headlined “Conrad the Great.” For Die Welt, Adenauer is “the chancellor Germany needs again today.”

Even the political magazine Der Spiegel, which Adenauer once denounced as a “rag,” which he accused of “treason,” and against which he supported an investigation in the wake of the so-called Spiegel Affair of 1962 — an attack on press freedom by his cabinet that caused widespread outrage and protest — gave his grandson Stephan Werhahn ample space for a favourable interview. Without critical questions, Werhahn had the opportunity to explain why Germany should “return to the policies of [his] grandfather.”

For nuanced opinions on Adenauer’s birthday, one had to look to smaller media outlets, such as the “Blog der Republik,” which soberly stated: “A complete picture also requires looking at those aspects of his rule that are often omitted in anniversary speeches: his authoritarian style of government, his problematic handling of the Nazi past, and his willingness to subordinate democratic principles to the preservation of power.”

Of course, everyone knows Adenauer’s legacy is complex. For example, the fact that German unity, and even East Germans themselves, weren’t particularly high on Adenauer’s list of priorities is generally acknowledged. He prioritised “Westbindung” – tying West Germany firmly to the West, especially the USA, over reunification. The Tagesspiegel , for instance, writes that there was “once” an “intense debate about whether Adenauer had betrayed the unity of the nation,” but goes on to claim that this has now been “decided in his favour.” “Certainly, after the Wall was built, the Old Man didn’t rush straight to Berlin,” they admit, but so what? West German memories aren’t going to be tarnished by such things.

Of course, there were sound realpolitical reasons for Adenauer’s decision to prioritise Western integration over German unity, but it also stemmed from an instinctive aversion. He was a Cologne native, i.e. from a western area that had been placed under Prussian control in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars. Prussia was abolished in 1947 but its shadow lived on in Adenauer’s heart. East Germany now occupied much of that space.

Adenauer had encountered the German East (in the geographical sense of that word) first as a Prussian superpower. During his time as chancellor (1949-1963) it was under Soviet control. As a staunch anti-communist, he may well have found that even more unpalatable. Adenauer is said to have spoken of an “Asiatic steppe” that for him began as early as Braunschweig. As soon as his train crossed the River Elbe, he is said to have drawn the curtains so he didn’t have to look at the East. One can interpret this however one likes. But the debate surrounding the history of remembrance is far from “decided”, especially if one expects East Germans to embrace the founding history of West Germany as their own and to celebrate its key figures and commemorative days.

Another point that continues to be hotly debated in historical scholarship regarding Adenauer is his decision to integrate numerous former Nazis into the structures of the Federal Republic of Germany. This personnel continuity was at least described as “problematic” in the Frankfurter Rundschau this week (while omitted by many other birthday articles). But the FR also ultimately weighed it up against the so-called Luxembourg Agreement of 1952, which marked the beginning of (West) Germany’s reconciliation with Israel.

Other arguments can be made for the reintegration of former Nazis, for example, that the doctor, the general, or the teacher could not be dispensed with, even if they had previously dedicated their efforts to Hitler. But did this really justify appointing people like Hans Globke, who was Adenauer’s long-serving head of the Federal Chancellery, even though he had been a co-author of the Nuremberg Race Laws and other anti-Semitic legislation of the Nazi era? However, one may answer that question, to me, this is such a big issue that it shouldn’t be omitted from pieces commemorating Adenauer today.

Now, before you think this is some angry East German ranting about West German history, let me remind you at this point that I consider Adenauer one of the most capable politicians in German history. However, as a historian, I find the increasing romanticisation of this period a little troubling.

Even the leadership of the left-liberal Green Party decided in 2023 to include an Adenauer quote in their election manifesto – the only quote, mind, in a pamphlet over 100 pages long – until it was removed because someone in the party’s grassroots remembered that Adenauer was a staunch, Catholic conservative whose views of women didn’t match the feminist outlook of the Greens. Nor do they think favourably of his rehabilitation of Nazi elites or the aggressive way he dealt with Social Democrats, including future Chancellor Willy Brandt. Really, it turned out, very little Adenauer fit the party’s self-image. Yet, he’s clearly sprung to mind when they looked for inspiration for a reset.

It is telling that Adenauer was viewed far more critically during his lifetime than he is today. For example, in 1961, when he was still chancellor, Der Spiegel accused him of deliberately ruling over a politically apathetic populace with his autocratic leadership style. “A spirit of political responsibility, of contributing and thinking critically, is absent in Germany today,” the magazine complained, concluding: “That Adenauer made no attempt to encourage and awaken this spirit is perhaps his most serious failing.”

The SPD, and especially opposition leader Kurt Schumacher, accused Adenauer of being the “Chancellor of the Allies,” who was deliberately deepening the division of Germany. Schumacher also felt that workers were being shortchanged in Adenauer’s system. While that demographic soon earned more money thanks to the economic miracle the country enjoyed post-war, higher education remained largely inaccessible to them. According to a 1965 study, the “upper and lower lower classes” made up only 5.4% of the student body at universities, even though they constituted well over half the population.

There’s no need to dwell on all of this on his 150th birthday, but it’s remarkable that Adenauer’s image today is more positive than ever. This has more to do with the times we live in than with new historical insights or sources. The West as a whole is struggling. The German economy is stagnating. According to polls, Adenauer’s conservative party (which is also chancellor Friedrich Merz’s party) would only garner half the vote share today that Adenauer achieved at the height of his power. Today, Germany can’t even agree on who its enemies and friends are. In contrast, the Adenauer era appears clear and optimistic: The enemy was in the East. The economy was booming. Men, women, workers, civil servants – everyone had their firm place in society.

Complicating this nostalgically idealised image with “yes, but” thoughts was tolerable for as long as certain fundamental certainties existed and the political, economic, and social structure of the “old Federal Republic” was still taken for granted. But in our current era, where everything seems to be in question, from prosperity to biological sex, many indulge in the comforting notion that there was once a time when everything was better and simpler. Inconvenient truths become a disruptive factor.

And now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to raise a glass to Konrad Adenauer’s birthday. As an influential architect of the post-war order in West Germany, he has earned his place in collective memory. But I’m going to cautiously test whether it’s possible to hold several thoughts in one’s head simultaneously without immediately despairing of the present.

In that spirit, here’s to Konrad the Complicated!

This is a translated and lightly edited version of my column for the Berliner Zeitung this weekend.

Great piece on a complex issue. For a country traumatised by its recent past and threatened by its immediate neighbour I imagine that it was understandable that the calming presence of an ‘elder statesman’ was reassuring, no matter how cranky or contradictory he was if you looked below the surface. But that is what historians do, and thank you and your profession for that.

That there is currently a wave of popular (populist) nostalgia for the man is a symptom of our insecurities in this fractured world, but, again, we need our historians to keep on asking the difficult questions.

Superb again Katja. I studied German post war politics but still learnt so much from your piece.