She escaped the Nazis and became a titan of British journalism: the eventful life of Hella Pick

... and what it reveals about antisemitism today.

Earlier in the week, I took part in a panel discussion on ‘Women in Journalism’ at the Residence of the Austrian Ambassador in London. While the topic certainly inspired a lively debate, for instance around the question as to whether class or gender is a bigger determining factor for the prospects of aspiring journalists, it was hardly controversial. And yet, I and the other panellists had been asked not to share information about the event on social media in advance due to the ‘associated security risks.’

The reason for this valid concern was not the topic of debate but the framework under which it took place. The event was the first in what is to become a series of lectures held in honour of the British-Austrian journalist Hella Pick CBE, who spent 30 years reporting on foreign affairs for The Guardian at a time when this was still largely a male profession. But Pick stood out in other ways too. In the words of her former employer, ‘she was a minority several times over – a woman, a refugee and a Jew.’

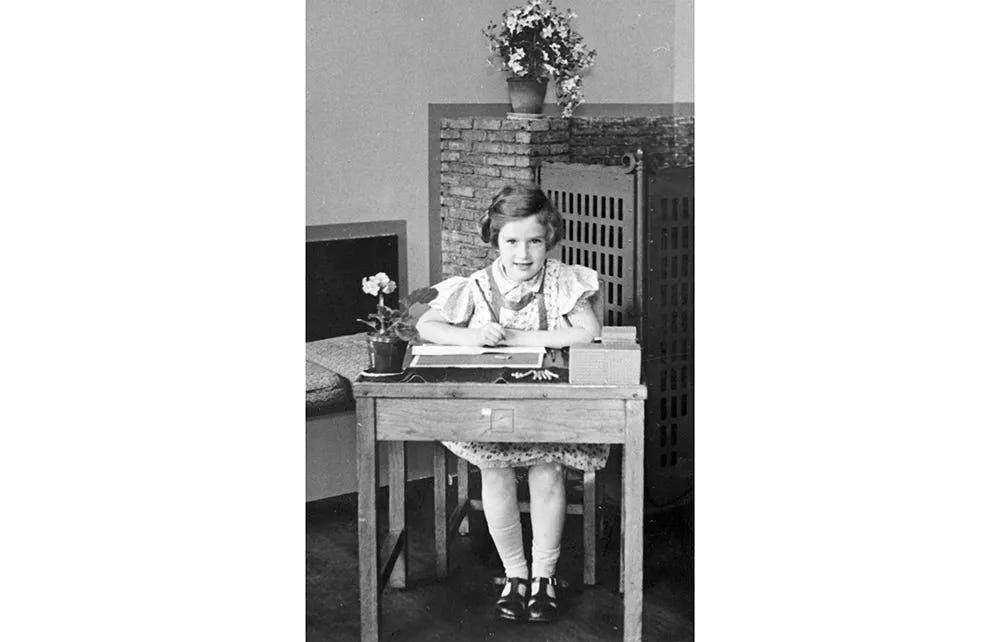

Hella Pick was born in Vienna in 1929 and, having been born into a middle-class family, lived a fairly sheltered life. She remembers playing in the park and going to school – a perfectly normal childhood. Then came the Anschluss, Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria in 1938. This dramatic change subjected her and all Jews in the country to severe repression and a permanent threat of violence.

Today, most school children in Western countries are taught about the Holocaust and its build-up in the 1930s. It’s meant to be a lesson not just in history but from history; a lesson in what happens when discrimination and racism are allowed to spiral out of control. When I was at school in Germany, we studied this era three times as part of the secondary school curriculum. I have since visited the sites of many former German concentration camps, including Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald and Auschwitz-Birkenau. And yet, the fact that never ceases to astonish and horrify me, is the idea that people were persecuted not for what they had done but for who they were.

Take Hella Pick. She was not even nine years old when Austria became part of Nazi Germany, and yet she became the target of repressive laws and measures and of the rampant antisemitism displayed by many of her fellow Austrians. She was a child, posing no threat to anyone. Yet Nazi ideology saw in her an imagined danger to the social, economic and political health of the national body, one that had to be cut out. An absurd concept, yet one that inspired many Europeans to participate in the Holocaust.

Daniel Finkelstein, whose mother Mirjam came from a German-Jewish family and was incarcerated in Nazi concentration camps as a child, described this phenomenon in an interview with me as ‘conspiracy theories that society is being controlled by an evil elite which needs to be defeated so that the true spirit of the people can be reflected…The concept was elastic enough that both my parents, even though they were 10 years old, were considered part of this elite.’

Hella Pick and her mother became enemies of the state they called home. They looked on helplessly as shops were vandalised and Jews arrested and murdered during the so-called Night of Broken Glass on 9 November 1938. In Austria, this pogrom took a particularly brutal form. Almost all of Vienna’s synagogues were destroyed, burnt down as fire brigades and citizens watched. Thousands of Jewish men were arrested and taken to concentration camps.

This was the moment at which many Jewish families realised the mortal danger they were in – a scramble for visas began to get out of the country to safety. The Jewish population in Austria made up around 4 percent of the population (compared to less than 1 percent in Germany). In Vienna, 9 percent of residents were Jewish. By December 1939 only around a quarter of Austrian Jews were still in the country.

Hella Pick’s mother too was gravely concerned. She had been arrested by the Gestapo, the Nazis’ infamous secret police. She was released the next day. This was a common method used to frighten Jews into leaving, but many found this difficult to do. Other countries had extremely strict immigration rules and latent antisemitism was rife around the world. Whilst speaking at the 1938 Evian Conference conference, which had been arranged to address the issue of German and Austrian Jewish refugees, the Australian delegate reflected the thoughts of many of his fellow attendees when he said: ‘As we [Australia] have no real racial problem, we are not desirous of importing one by encouraging any scheme of large-scale foreign migration.’

For Pick’s mother, this meant she had to take any chance that she could to get her daughter to safety, even if it split them up. She put Hella on a list for Britain’s new immigration scheme, the Kindertransport. The programme lasted for nine months before the outbreak of war and waived immigration restrictions for unaccompanied children up to the age of 17 under certain conditions. It came on the back of an appeal made by a group of British leaders from different communities, including Quakers and Jews, directly to Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in the wake of the ‘Night of Broken Glass’. In total, the UK took in nearly 10,000 children.

Such figures hide the human dilemmas and tragedies behind them. What was going through the mind of Pick’s mother as she put her 10-year-old daughter on a train in March 1939, not knowing if she would ever see her again? The despair was such that parents would rather be separated from their children if it meant saving their lives. When the British government made inquiries in Germany to determine whether the Kindertransport scheme would work, they found that nearly every parent they had asked said that they would be willing to send their children unaccompanied and stay behind if that was the only way to save them from Nazi tyranny.

For the Kinder themselves, the experience was often traumatising too. They had no understanding of what was happening and certainly, like everyone else in 1938 and 1939, no conception that six million Jews would soon be murdered by Nazi Germany and its collaborators. Alone in a foreign country whose language they often didn’t speak when they arrived (Pick greeted her host family upon arrival with a cheerful ‘Goodbye’ as this was the only English word she knew), raised by foster families or in homes and hostels, they desperately waited for news from loved ones stuck in their home countries. Pick was lucky. Her mother managed to get a visa three months later and joined her in Britain. Many other Jewish children would never see their parents again.

Yet the scale of this human tragedy pales in comparison with those children who did not make it out in time or managed to survive through being hidden. During the Holocaust, 1.5 million children were murdered, the vast majority of them Jewish. They were never targeted for any crimes they were supposed to have committed but for the fact that they were born into Jewish families.

It was striking for me to think that a lecture held in honour of Hella Pick’s work as a titan of British journalism, a discussion around what it meant for her as a woman to break into a largely male domain, would still be considered a security risk in London in 2023. The event could have been targeted not for what was said but for who attended it and who organised it.

The debate was hosted in collaboration with the Sussex Weidenfeld Institute of Jewish Studies, and some members of the organising team and the audience were Jewish. Before and after the lecture, some of them talked about shocking acts of threatening behaviour and intimidation they had experienced recently, particularly in the last few days due to the terrorist acts committed by Hamas in Israel and the escalating tensions since. The Metropolitan Police spoke of a ‘massive increase’ of in antisemitic incidents in London.

One woman told me the Jewish school her daughter attends in London was closed following open threats made to it. Another said a work colleague had praised her in the office kitchen for being ‘not overtly Jewish’ given what ‘Israel is doing to Palestine.’ Many Jews today are once again the subject of prejudice and threats not because of anything they have done but for being Jews, be that primary school children on the way to their lessons or employees at their place of work.

It was eye-opening to hear Hella Pick’s closing remarks at the Austrian Residence in Belgravia, and her words still rang in my ears as I walked into Liverpool Street station later that night. When I sat down on a bench in the middle of the large forecourt to wait for my train, I found myself looking directly at the smaller of two memorials there to the Kindertransport.

'Für das Kind’ it says on the plinth underneath the bronze statues of a little boy and a girl, both looking somewhat uncertain about the future that lay ahead for them in their new home, Britain. Hella Pick too arrived here 84 years ago. A new life began, one full of new opportunities and challenges. It is a sad thought that a fraction of the old challenges have remained too.

Thought provoking piece. Antisemitism is the persistent shame of Europe and the UK. While we should give thanks for the Kindertransports it is to our shame, the UK, that we did not make it easier for their parents to come here. Essentially on your recommendation I bought Danny Finkelstein’s book Hitler, Stalin, Mum and Dad; I highly recommend it. I have read many books about The Holocaust and so antisemitism is one of the few things I feel strongly about thus I find the commentary from many demonstrations absolutely infuriating. The UK should outlaw blatant Holocaust denial. It would send a firm message.

How desperately sad that in this day and age religious background is still an issue , have we learnt nothing 🙁