Start the year with some German escapism

Happy New Year, dear readers or as they say in Germany: “Frohes Neues”!

I hope your head doesn’t hurt too much this morning because this post is about alcohol, I’m afraid…and other headache-inducing things like nazi-era films and memory politics. I know, heavy themes on New Year’s Day, but presumably you didn’t come to a German history blog for light reading. Also, the nazi-era film is a comedy…

Which brings me directly to the theme of the first post of 2026: a much-cherished winter and New Year’s Eve tradition of melting rum-soaked sugar into mulled wine while watching a 1944 film meant to cheer Germans up as the war was going very badly for them. The film and the drink share the same name: Die Feuerzangenbowle, which literally translates as “The Fire-Tongs Bowl” and more loosely as “The Punch Bowl”.

The drink involves quite an elaborate ceremony involving fire and hot wine, which is why it has remained a popular thing to do with friends, family or in public settings during the cold winter months, particularly in the build-up to Christmas or on New Year’s Eve. You heat a dry red wine and infuse it with cinnamon, cloves and orange peel, creating a mulled wine. In my recipe, you also add a bit of orange juice, but that’s optional.

Then comes the fiery bit: you place a metal grate (or a pair of the tongs that gave the drink its original name) across the wine bowl and place a sugar loaf (in German Zuckerhut or “sugar hat”) on it. Then you drench the sugar in dark, high-alcohol (at least 54%) rum and set it on fire.

Sit back and watch the blue flames dance across the sugar, caramelising and melting it until it begins to drop into the mulled wine. Add more rum as required (with a ladle rather than straight from the bottle to avoid accidents) until all the sugar has gone. Then pour the mixture into mugs for everyone to enjoy while keeping the rest warm over a burner.

It’s a lovely communal ritual that most people enjoy in its own right rather than just for the very warming drink it produces. I went so far as to take my fire bowl set to the UK when I first moved here (though obtaining sugar loaves isn’t always easy). It wasn’t a tradition in my family so much, but it’s a big thing on university campuses, and that’s where I first learned to appreciate it: as a student in Jena, one of the oldest universities in Germany and one very conscious of traditions. The Feuerzangenbowle was no exception.

The drink and the ritual are closely linked to the 1944 film of the same name, which is usually shown on campus in the largest lecture hall or in private homes, with friends and family gathered around the punch bowl as they watch.

Starring the popular German actor Heinz Rühmann, the plot begins with a group of men gathered around a fire-punch bowl. In a nostalgic mood, they wax lyrical about their school days, but one of them, the writer Johanns Pfeiffer (played by Rühmann), can’t join in because he was privately educated at home. He decides to catch up on this vital life experience. With his youthful face (though Rühmann was already in his 40s when he played the part), he finds it easy to masquerade as a secondary school student and joins a small-town, all-boys grammar school. The film is about his comical interactions with his teachers and fellow students.

What makes the movie such a “masterpiece of timeless, cheerful escapism,” as one critic put it, is its innocence. It may have been released in 1944, produced by a Nazi film industry that left nothing to chance, but there isn’t a trace of politics in it.

It’s set in a non-specified moment of “the good old days”, most likely during the Kaiser-era, around the turn of the century, and there is no overt commentary on politics, society or anything else beyond the day-to-day life of the rejuvenated Pfeiffer in it. It’s all about the pranks the boys play on their teachers, the comical, old-fashioned, but ultimately well-meaning nature of the Prussian staff and about nostalgia. This is precisely why it has endured across so many different eras and regimes without serious criticism.

When it was first produced during the dying years of the Nazi regime, it was in the context of a directive by propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels to produce entertaining, escapist films for a war-weary population that wasn’t supposed to think too much about what was going on. Harking back to a time before both world wars, a time many Germans had begun to think of as the good old days when their nation had been proud, undefeated and prosperous, it hit a nerve.

1944 was post-Stalingrad. Families had lost countless men and boys on the frontlines. The regime was viciously lashing out against real and imagined opponents at home. Rationing was back. Bombing, too, had brought the war home.

The filming itself was interrupted time and again by bombing raids. “Working on it was like dancing on a volcano,” one of the actors later remembered, adding, “we were glad every time we had survived the bombs again.” An hour and a half spent in a coal-heated cinema away from the omnipresent propaganda, war and misery, laughing at the innocent pranks of Prussian schoolboys must have been unimaginably blissful.

Yet, Nazi morals touched every aspect of life, even those that were supposed to give the population some respite from them. Education Minister Berhard Rust fretted about the film, worried that its ridicule of stiff, old-fashioned teaching styles might undermine teachers’ authority, even as wartime had already disrupted schooling routines by drafting teachers for frontline service.

The star of the film, Rühmann, was convinced Rust was wrong. He boarded a night train, a copy of the movie in his pocket, and took it personally to the so-called Wolf’s Lair, Hitler’s military HQ behind the Eastern Front.

There, Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring discussed the matter with Hitler. According to Göring, the Führer asked: “Is this movie funny?” Göring admitted that he had laughed several times while watching. Hitler responded: “Then this film must instantly be released to the German people.” Goebbels was told to approve Die Feuerzangenbowle, and it premiered a few days later, in January 1944, in Berlin – in the morning, since an air raid alarm was expected in the evening.

If you’re wondering why it isn’t controversial today to show and even celebrate a film produced by the Nazi regime and officially deemed “artistically valuable” by it, let me tell you what happened to it after the war. It took 20 years for it to be shown on television in post-war Germany, and when it was, it was the socialist East Germany that broadcast it first. When West Germany did it too in 1969, over half of TV viewers, or 20 million people, tuned in.

Today, in the reunified country, the movie has cult status and lines from it have entered everyday parlance. There is a famous scene, for instance, where Pfeiffer first enters the school, pretending to be a new student from Berlin. His teacher pulls out his notebook to add his name to the list of students and asks whether Pfeiffer is spelt “with one ‘F’ or two?” Pfeiffer smiles wryly and answers: “with three, Herr Professor…one before the ‘ei’ and two after the ‘ei’” That’s become a classic and no doubt one that anyone actually called Pfeiffer hears on a weekly basis.

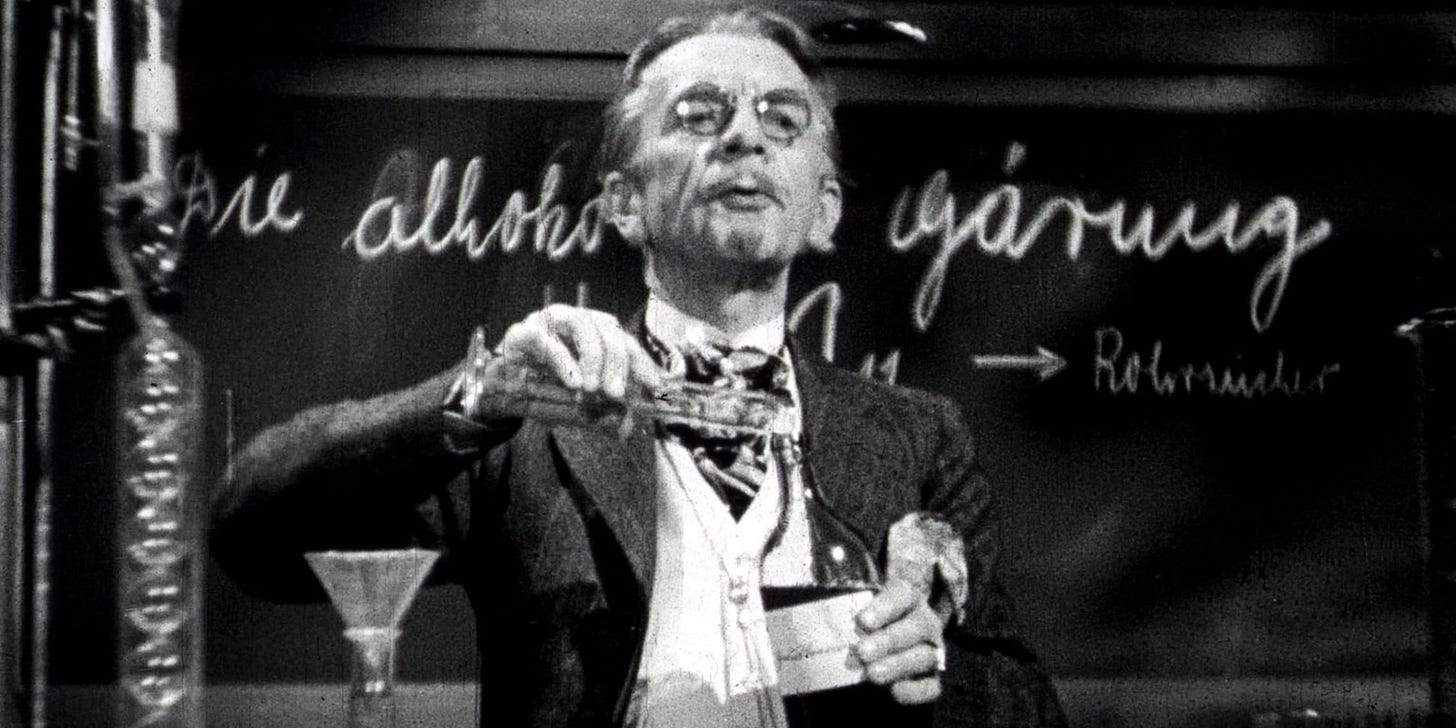

In another famous scene, the teacher explains in a Chemistry lesson how alcohol is made. He brags to his colleagues about how innovative his teaching method is. Every year, he brings a bottle of homemade blueberry wine into his lesson “so that everyone can see for themselves how wonderful it tastes.” He gives a glass to the first student and warns, “Careful! Everyone takes just one tiny sip or it’ll go straight to your head!” I leave it to your imagination to work out in what contexts that line is recited most often in student life.

Of course, some critics have pointed out that the film isn’t apolitical at all. Rühmann was one of Hitler’s favourite actors – though one of Germany’s, too, with an immensely successful post-war career in West Germany that culminated in his being named the “greatest German actor of the century” in 1995.

Rühmann himself knew what his role was in Nazi Germany, commenting later: “I was needed. The powers that be could see that a certain sense of humour needed to be spread to the people. For that, they used a comedian, so to speak, an actor, who had already been able to make people laugh beforehand.” Some of the other actors were drafted immediately after filming and didn’t even live long enough to see the release.

And yet, the film’s appeal lies precisely in its timeless escapism. It was on TV once more when I was in Germany for Christmas, and we watched it with four generations. My grandmother, who was a child when it was first released and who has terrible memories of hiding in bomb shelters with her frightened younger brother around that time, laughed about Pfeiffer’s antics just as much as I did, who was lucky enough never to have experienced war or dictatorship firsthand. If it was funny enough to take people’s minds off existential fear and misery in 1944, it’s no wonder it still makes people laugh today.

And on that note, I wish you a very happy New Year! Go armed with knowledge of the past into the future and try to make the best of it. I hope 2026 brings you all the joy, success and health you are hoping for, and that I will continue to have the twice-weekly privilege of accompanying you on your journey with my German musings.

Frohes Neues!

Oh nice one Katja and happy 2026.Thursday and Sunday are no longer Thursday and Sunday but Zeitgeist day.

May the tales of the never straight forward journey of Germaness continue. Germaness is that even a word ..