The Iron Chancellor in Love

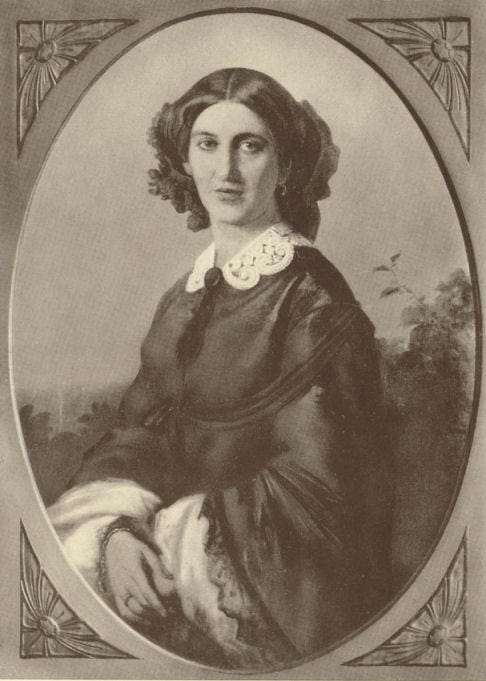

Johanna von Puttkamer and Otto von Bismarck

As it’s Valentine’s Day this weekend, I thought I’d treat you to the story of a relationship that shaped German history. I doubt you’ll find it very romantic, but it certainly doesn’t lack depth or feeling. I speak, of course, of Otto von Bismarck and his wife Johanna von Puttkamer.

I doubt many people could name Johanna. When people think of Otto von Bismarck, they tend to picture him as a solitary figure, as the ruthless architect of German unification. Bismarck isn’t remembered as a family man or husband but as the Iron Chancellor, a towering Prussian in a spiked helmet who bent the fate of Europe to his design by means of blood and iron. To be fair, I can’t really complain about that, having made a modest contribution to this view myself in recent years…

And yet, by the side of this formidable statesman stood a woman whose influence may have been much quieter but in a way no less enduring. To understand Bismarck fully, you can’t just look at the wars, treaties and domestic battles that shaped his political life. His marriage, too, played a crucial role that extended far beyond the private sphere. It steadied, softened and at times redirected him.

Bismarck met Johanna in the 1840s through Pietist religious circles in Pomerania. It wasn’t exactly love at first sight. He’d been introduced to this circle by a school friend of his called Moritz von Blanckenburg, and it was Moritz’s fiancée, Marie von Thadden, that he was smitten with. The attraction was mutual. Marie was fascinated by Bismarck’s sharp mind, his bold personality and the way he brazenly talked about his lack of conventional religious faith in a circle full of devout Christians.

Despite their feelings for one another, Marie couldn’t and wouldn’t break the betrothal with Max. The couple got married in 1844. But Marie and Moritz had a cunning plan to cheer up the heartbroken Bismarck. At their wedding party, they placed Marie’s friend Johanna von Puttkamer next to him at the table. Bismarck couldn’t get over Marie, though, and appears to have been quite mopey. Moritz felt the need to encourage him to give Johanna a chance, “Come and take a look at her!” he joked, “If you don’t want her, I’ll take her as my second wife.”

Bismarck slowly warmed to Johanna as the pair of them went travelling with Marie and Moritz. But in the end, it was Marie’s tragic death from an inflammation of the brain in November 1846 that brought an end to his deliberations. A month later, he wrote to Johanna’s father to ask for her hand in marriage.

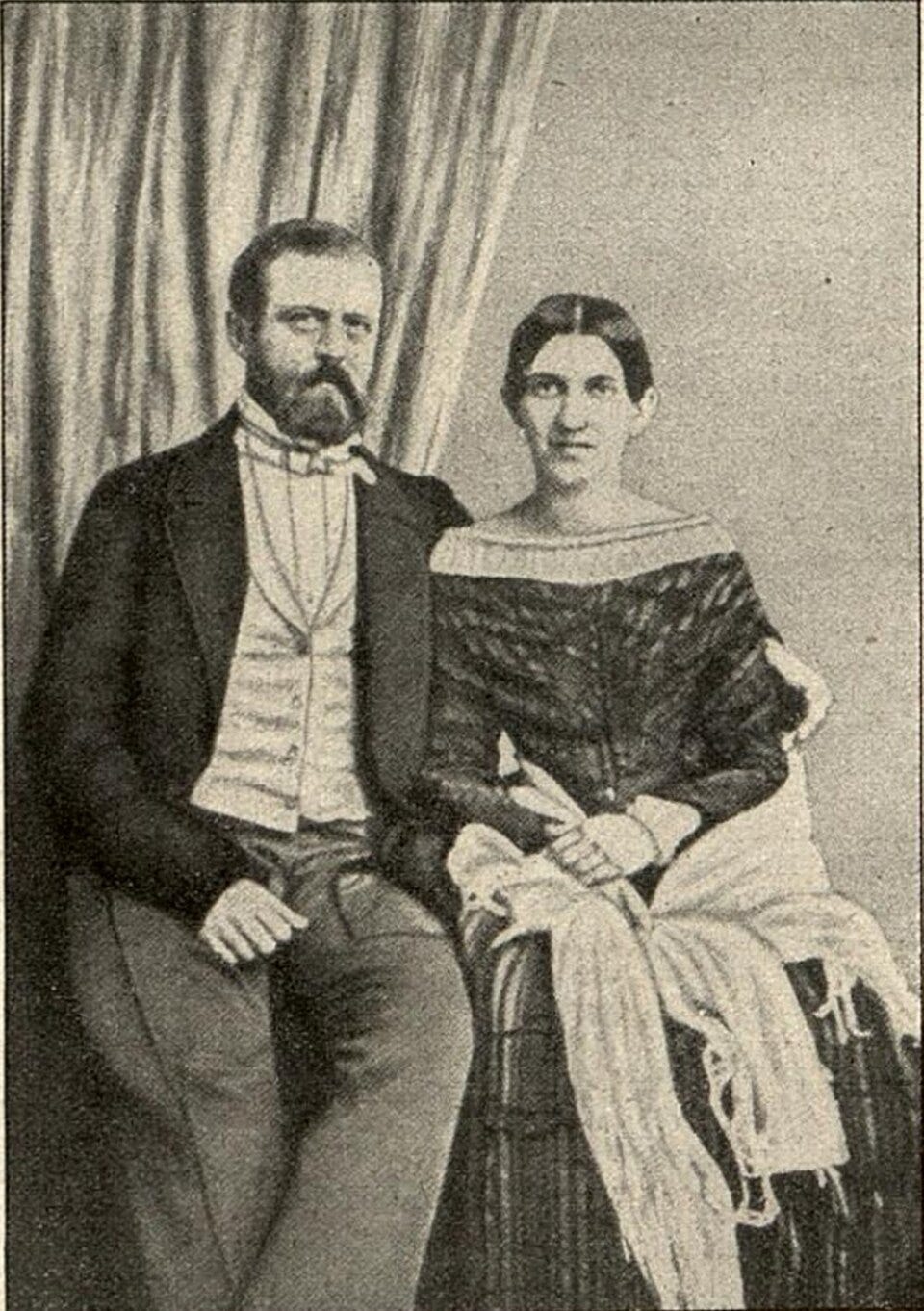

The couple weren’t exactly a match made in heaven. She came from an old Prussian noble family and was deeply devout, shaped by a Protestant faith that emphasised humility, duty and moral seriousness. Bismarck, at that time, was known more for his volatility than his discipline, to the point where neighbours referred to him as the “crazy junker”. As a young landowner in his twenties and thirties, he drank heavily, gambled and cultivated a reputation as a fiery conservative with a taste for confrontation. His emotional life was stormy, oscillating between exuberance and despair.

The marriage marked a true turning point. It rooted the wild, disorientated and heartbroken young man emotionally and psychologically. Bismarck later wrote that Johanna had brought “peace” into his life. This would prove to be of historical importance because the wedding in 1847 coincided with his accidental entry into politics as a delegate to the regional parliament when he’d been asked to step in for another member who could not attend due to illness. He was utterly enthralled by the experience, enjoying the intrigue, plotting and oratory battles that came with political life. Politics, he confessed to a friend, had him “in an uninterrupted state of excitement that barely allows me to eat or sleep.” Johanna provided a domestic anchor just as he stepped onto a larger political stage.

From the beginning, their relationship was marked by contrast. Bismarck was expansive, theatrical and often caustic. Johanna was reserved, pious and steady. She had little interest in politics as a subject of debate, and unlike some 19th-century political spouses, she did not attempt to shape policy or cultivate salons. Yet her very distance from the political fray proved important. Bismarck could retreat to her as to a sanctuary. He wrote her long letters from diplomatic postings in Frankfurt, St. Petersburg and Paris, letters that reveal a side of him far removed from the Iron Chancellor persona. They were the letters of a homesick man, self-doubting, even tender.

When Bismarck served as Prussian envoy to the German Confederation in Frankfurt in the 1850s, he found the atmosphere socially and politically exhausting. He complained of intrigues and petty rivalries. His letters to Johanna during this period are full of yearning for the quiet of their country estates. “Without you,” he once confessed, “everything here is colourless.” These were not empty flourishes. He frequently suffered from bouts of depression and physical ailments, including insomnia, digestive troubles and nervous strain. Johanna’s presence and correspondence were a stabilising force.

He didn’t always repay her thoughtfulness in kind. In 1852, he provoked a political adversary by insulting the man’s mother (yes, that was a thing already…) and was challenged to a life-or-death duel. Johanna was pregnant at the time, but this didn’t cause Bismarck to think twice about accepting the shootout. He only asked his brother-in-law, Arnim-Kröchlendorff, to look after her and the baby should the worst come to pass.

Johanna’s importance became even clearer during the great crises of the 1860s. As Prime Minister of Prussia, Bismarck confronted a constitutional conflict between the King and the liberal-dominated parliament over army reform. The struggle was bitter and protracted. A lot was at stake. In 1862, he famously told the delegates that the great questions of the day would be decided by “blood and iron,” not by their debates or majority decisions. Yet behind this public bluster and defiance lay intense psychological pressure. There were moments when Bismarck considered resignation. History would have taken a very different turn had he thrown in the towel there and then. In such periods, Johanna’s unwavering, pious belief in her husband’s divine mission fortified him.

Bismarck’s own beliefs were messy and laced by doubt, whereas his wife’s were clear and strong. She saw his political role through a religious lens. For Johanna, her husband’s work was part of a providential design. That conviction gave Bismarck both comfort and a kind of moral framing. He did not become gentler in politics. His “unification wars” against Denmark, Austria and France were calculated and ruthless. But he carried with him her sense that he was acting in accordance with a higher duty. Johanna’s faith reinforced this self-understanding.

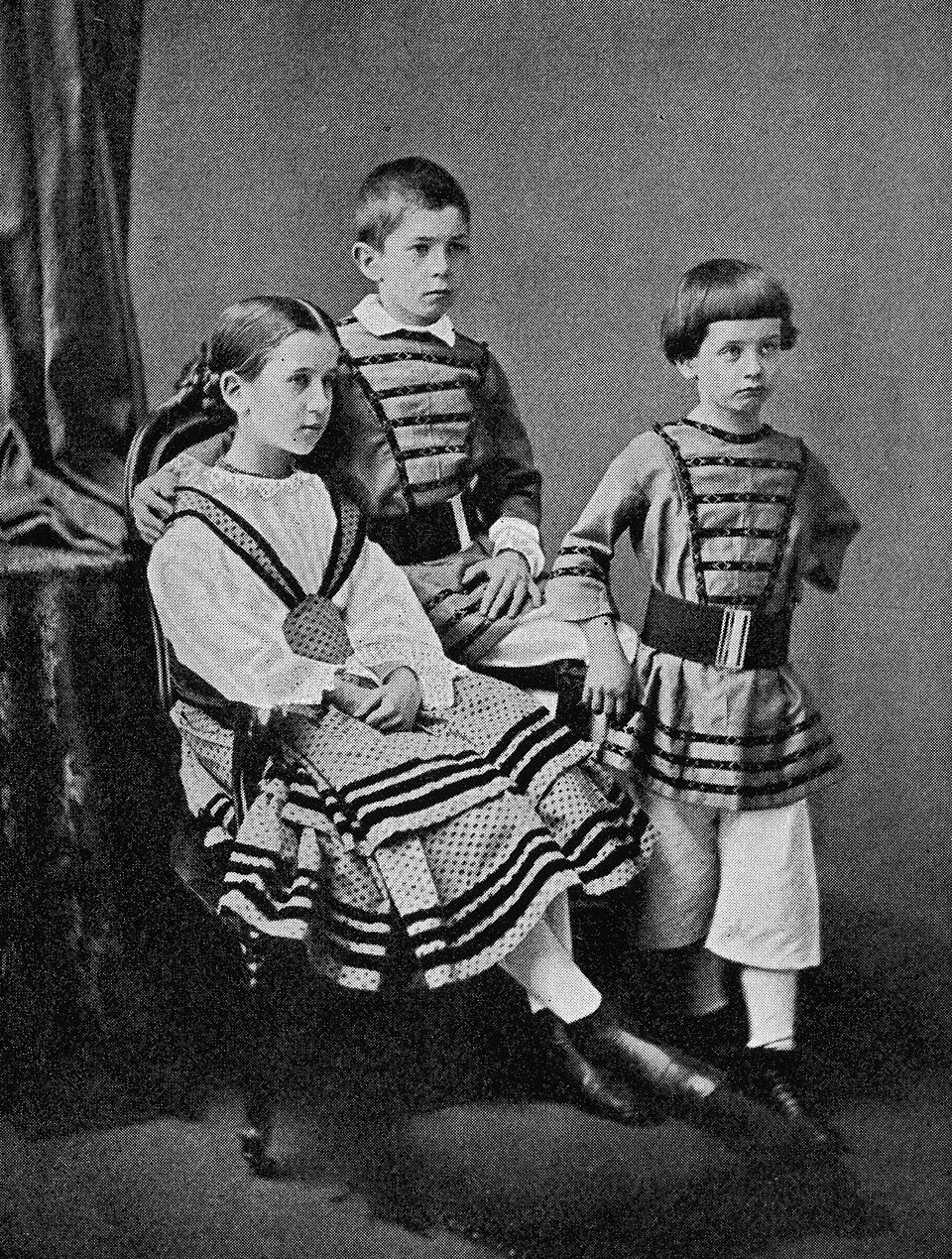

Their offspring also mattered. The couple had three children: Marie, Herbert and Wilhelm. Bismarck was deeply attached to them. Visitors to their country estates often remarked on the contrast between the domineering statesman in Berlin and the affectionate, playful father at home. Johanna presided over this domestic sphere with quiet authority. She managed the household, maintained the social obligations of their rank and ensured that the family estates functioned smoothly even during her husband’s long absences.

Her social role in Berlin, especially after Germany was founded as a nation state in 1871, was understated but significant. As the wife of the country’s first-ever Chancellor, she became a symbolic figure in the imperial court. Unlike the glamorously dominant figure of Empress Augusta or later the sharp-tongued Empress Victoria (Queen Victoria’s eldest daughter), Johanna did not cultivate a public persona. She preferred simplicity and religious devotion to courtly display. Yet this very modesty enhanced Bismarck’s image among conservatives, who valued traditional family virtues. She embodied the Prussian ideal of domestic womanhood: loyal, pious, unpretentious.

There were also moments when Johanna’s influence was more direct. During Bismarck’s Kulturkampf, his struggle against the Catholic Church in the 1870s, his policies were severe. Though Johanna was firmly Protestant, she is said to have worried about the harshness of the measures. While there is no evidence that she dictated policy, her moral sensibility formed part of the intimate environment in which Bismarck weighed his decisions. Over time, he moderated aspects of the Kulturkampf, driven by political calculation but also, perhaps, by fatigue with conflict on multiple fronts.

In later years, as Bismarck clashed increasingly with the young Kaiser Wilhelm II and finally fell from power in 1890, Johanna remained his refuge. Retirement allowed him to withdraw from the pressures of office, but not from his combative temperament. She continued to provide the steady companionship that had defined their marriage for more than four decades.

Bismarck’s emotional devotion to his wife didn’t always translate to sexual faithfulness. Johanna knew and tolerated her husband’s passionate affair with Katharina Orlowa, the young wife of the Russian ambassador to Belgium. The lovers nearly died together when they got into trouble swimming off the French coast. They were lucky to have been fished out of the water by a lighthouse keeper. Bismarck even wrote to his wife about this, joking that he had “gulped down some seawater”.

Affairs notwithstanding, the letters Bismarck and Johanna wrote to one another over the years are full of emotions, insights and mutual trust. They are an invaluable source for us as historians and offer fascinating, human glimpses into the 19th century. In this way, too, Johanna’s presence in Bismarck’s life has shaped history — and the way we see it today.

Johanna died in 1894. Bismarck, who had faced down emperors, outmanoeuvred great powers and unified the biggest country in Europe by brute force, was devastated. He survived her by four years, but friends noted that he seemed diminished and pale. The Iron Chancellor without his anchor was a lonelier, more brittle figure. When he lay on his deathbed in 1898, his last words were not about Germany. With his last breath, he whispered, “Please just let me see my Johanna again.”