The Remarkable Story of Adidas

And why it isn't often told

When the American rapper and fashion designer Ye, formerly known as Kanye West, made a number of antisemitic remarks last year, his business partners came under enormous pressure to cut ties with him. Instagram and Twitter suspended his accounts, clothing retailer Gap cancelled its 10-year contract after only 16 months and the bank JP Morgan ended its business relationship with him and his Yeezy brand.

But for one of Ye’s partner companies his comments, which included praising Adolf Hitler and denying the Holocaust, had the potential to inflict severe reputational damage even after ties had been severed. Adidas, the second largest sports brand in the world (after Nike), generated $2 billion in annual sales through the Yeezy brand, around 10% of total revenue. But painful as it may have been, breaking with Ye allowed Adidas to make a clear statement saying that it ‘does not tolerate antisemitism.’ It came at a time when newspapers had begun to dig deeper into the German company’s history and began to write about ‘its historical association with Germany’s Nazi Party.’

Last year, Adidas produced 420 million pairs of shoes worldwide. In the UK alone, 6.6 million people wear Adidas shoes. How many of these people take a new pair out of the box or slip on their trusted old trainers thinking, ‘I wish I knew more about the brand’s history!’ Very few, I would imagine, and that’s just how Adidas like it. When asked to comment on the company’s history in the wake of the Ye controversy, they declined.

It’s not that the story of Adidas is any darker than those of many other German companies old enough to have been around during the Nazi years. But Adidas has thrived on a reputation of innovation over the years, on its ability to reinvent itself, and for that it needs to travel light when it comes to historical baggage – hard to do when your back story is as interesting and full of ohhh-who-knew?! moments as that of Adidas.

Like many good stories, it all began with two brothers. Their names were Adolf and Rudolf Dassler and they grew up in the beautiful Bavarian town of Herzogenaurach. Their father was a shoemaker who earned his money in the local factories; their mother ran a small laundry. Adolf, called Adi by his friends, completed an apprenticeship in a bakery, which his father had urged him to do. But Adi’s real love was for sports, many of which he engaged in passionately: athletics, football, boxing, ice hockey and skiing among them.

Adi began to observe his teammates and opponents, and in a town specialising in shoemaking, the link between the two fields quickly came to him. If an athlete had shoewear adapted to their particular sport, they would have an enormous advantage over their opponents.

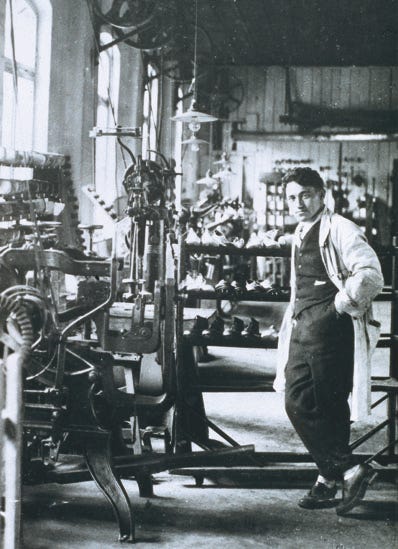

But before he could do anything about this idea, the First World War crossed his plans. He was only 14 years old when it broke out in 1914. But in 1918 he was called up for duty and was only released in 1919. He hadn’t forgotten his idea. With the few materials available in post-war Germany, he began manufacturing his first sports shoes in his mother’s scullery. This wasn’t easy. He collected remaining material from military stock, repaired shoes to raise funds and connected a bicycle to the machinery to keep production going despite the frequent blackouts.

Adi then began sending his first prototypes to local sports clubs who quickly began to recognise the value of specialised footwear and began ordering more. Adi’s brother Rudolf, who had become a policeman after the war, recognised the potential of the emerging enterprise and joined in 1924. As Adi continued to think and develop, Rudolf took over the business side. It worked. By 1928, the brothers produced 100 shoes a day in specialised premises and they had also begun to experiment with new technology for sport shoes: spikes.

When the Summer Olympics of 1928 in Amsterdam approached, the brothers were keen to use them as a platform. They gifted the German track and field athlete Lina Radke a pair of their spiked running shoes and she set the first officially recognised world record in the 800m event in them. Adi and the world felt confirmed in the belief that the right shoes could bring out the best in an athlete.

At the next Olympics in 1932 in Los Angeles, more athletes wore his shoes. Among the new fans was the American track and field athlete Jesse Owens, who would go on to win four gold medals in Adidas shoes at the 1936 Olympic Games in Nazi Germany.

When Hitler came to power in 1933, the Dassler brothers joined his party immediately and Adi held a position in the Hitler Youth, being involved in the local sports club. The company continued to thrive. By 1938, it had 118 employees and produced over 1000 shoes a day for eleven different sports. When the war began in September 1939, Adi and Rudolf were told to produce shoes for the Wehrmacht, the German army – 10,500 a month.

The brothers began to argue vehemently with one another. Rudolf’s focus was to make money while Adi wanted to focus on sports and development. When Rudolf was conscripted, matters became worse as he feared losing control in his absence. A bitter exchange of letters ensued that was to damage their relationship permanently. But in November 1943, their quarrel became meaningless as the Dasslers were told to transform their business to produce armaments for the war effort, making the so-called Panzerschreck, an anti-tank weapon. In the process, at least 9 forced labourers were used.

Adi and Rudolf never reconciled and went their separate ways after the war. While Adi resumed production in his premises, Rudolf founded his own company in 1948 which would remain his brother’s biggest rival for decades: Puma. The hostility between the two divided the town and even its football teams which were supplied by the two brothers respectively.

On 18 August 1949, Adi Dassler officially founded his own firm, using his nickname and the first three letters of his last name to form the acronym Adidas. On the same day, he also had the three stripes registered as the company trademark.

The brand would gain worldwide fame through West Germany’s growing sporting prowess. The football team won their first world cup in 1954 in the so-called Miracle of Bern. Only nine years after the end of the Second World War, Germans were broadcast around the world cheering a benign victory. And they did so wearing the first modern football boots with studs that could be screwed in at different lengths.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to ZEITGEIST to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.