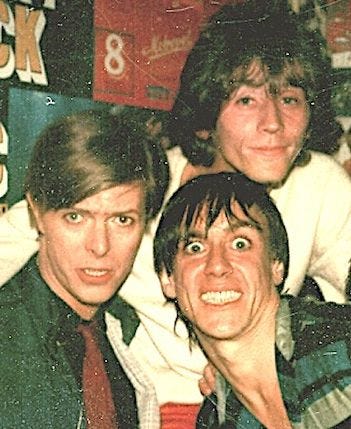

Walls, Krautrock and Fascist Flirtations: Bowie in Berlin

Ten years after David Bowie's death, what's left of his German phase?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to ZEITGEIST to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.