The Secret Life of Coffee in Germany

Of Ottoman trade routes, Hamburg warehouses and Vietnamese plantations

I’ve made a wonderful decision this week: I treated myself to a new coffee machine. Nothing fancy, just a simple filter coffee maker, but the upgrade to my trusty old one is that it can grind beans and has a timer. Now I can literally wake up and smell the coffee!

Just to be clear, this isn’t (just) about the caffeine. It’s about all the positive things I associate with the smells and sounds of percolating coffee, about the communal jug sitting on its hot plate for anyone to help themselves. The whole experience radiates everyday comfort to me.

Since I’ve moved to Britain, I realised that few people here share this sentimental attachment to filter coffee. It’s true that coffee consumption in the UK has gone up. Coffee has even taken over from tea as the UK’s favourite hot beverage, but Brits drink more instant coffee than most people on the planet, and they buy much of their brew from coffee shops and cafes (apparently 80% do this weekly). I guess that’s a result of tea having been so dominant for so long, so coffee culture comes in a fairly modern guise.

By comparison, official government statistics in Germany suggest that 82% of households have a coffee machine. While the good old filter machine is in decline, it remains the most popular choice, owned by over half of German households (the rest have mostly got fancy, fully automated machines or pad/capsule-based ones).

Those differing stats point to differing traditions. Coffee is to Germany what tea is to Britain. And this manifests in many ways, including economically. Despite not having the climate to grow coffee, Germany is one of the world’s largest exporters of coffee products. It simply imports enormous amounts of raw beans, roasts them and sells them on. If that isn’t great pub quiz knowledge, I don’t know what is….

But I appreciate that the notion of Germany as a coffee nation is counterintuitive. When people think of Germany, they tend to think of beer, bratwurst and pretzels. Yet Germany has quietly cultivated one of the most enduring and surprising love affairs with coffee.

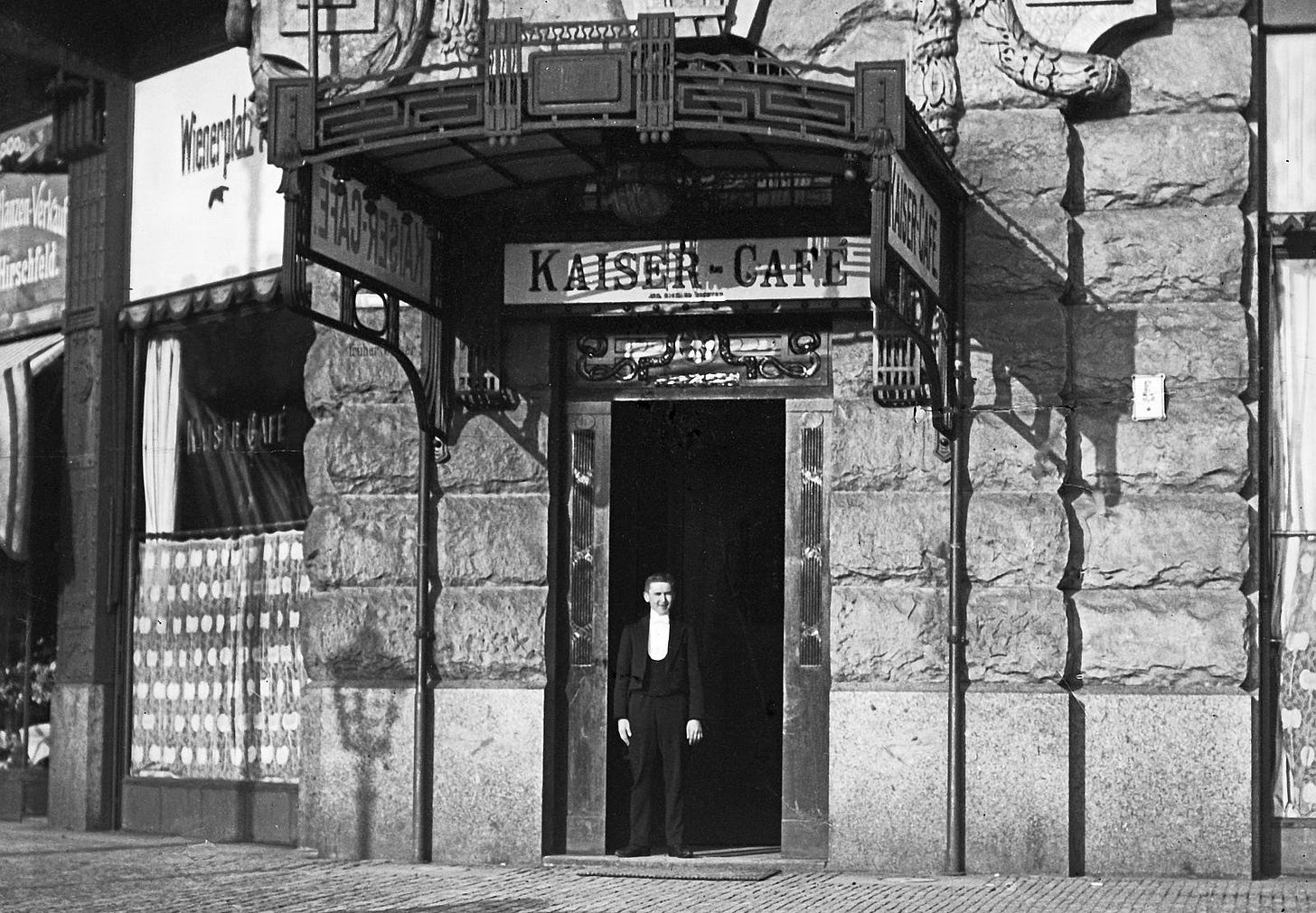

Coffee first drifted into the German-speaking lands in the 17th century, arriving via trade routes from the Ottoman Empire. By the 18th century, it had become fashionable among the wealthy elite, who enjoyed it in ornate coffee houses that doubled as social salons, especially in Vienna, where many still exist today. But these tastes quickly spread further north and west, too. By 1914, Germans accounted for one-third of worldwide coffee consumption, second only to the USA, which had 30 million more inhabitants.

One of the most fascinating chapters in Germany’s coffee story takes us to Hamburg, which has been importing coffee since the 18th century and today hosts one of the world’s largest coffee roasters, Tchibo. The city’s Speicherstadt district, with its maze of warehouses, celebrates the history of beans that travelled the globe before landing in German cups. Even today, you can visit roasters there and see the process before sampling a confusing array of coffees. I did that a few years ago and never wanted to leave the place again.

While researching for Beyond the Wall, I came to understand for the first time the political dimension of Germany’s attachment to coffee. When East Germany developed a serious supply problem during the Cold War and tried to fob people off with a terrible coffee mix, the grumbling became so loud that it frightened even a dictatorial regime into action. The government built a coffee industry from scratch in Vietnam, starting in the 1970 and 80s, aiming to secure a steady supply for its citizens. While the first yield was too late for the GDR, the venture was very successful for Vietnam, which still benefits from it today as one of the world’s largest coffee producers. The episode also shows just how serious East Germans were about their coffee — even when politics and geography made it difficult. Coffee was more than a drink. It was a small act of normalcy and comfort, hugely important to people living through a tumultuous 20th century.

If you know any Germans, you may have encountered one of our most comforting rituals: Kaffee und Kuchen. Translating to “coffee and cake,” this isn’t just an afternoon snack — it’s a cultural institution. Families and friends pause mid-afternoon to enjoy a slice of cake with a cup of coffee. It’s also an occasion to invite people over on weekends or for birthdays. Researching for my upcoming Weimar book, I found references to it time and again. As the storms of hyperinflation, the Great Depression and ruthless ideologies raged around them, people still took the time to sit down for a cuppa and some cake.

Coffee culture in Germany also reflects a deep love of quality and craft. While American-style coffee shop chains exist, many Germans favour freshly roasted beans, often sourced from specific suppliers and brewed in intricate home machines or at their favourite independent cafe. Speciality coffee shops have surged in cities like Berlin and Munich, blending traditional German precision with a modern barista culture. There are even cafés where staff will weigh, time and control water temperature for every cup.

It’s easy to forget, when sipping a cup in a bustling Berlin café, that Germany’s coffee culture is built on centuries of history, global trade and even geopolitical ambition. From the imported beans in Hamburg warehouses to East German-built plantations in Southeast Asia, coffee has woven itself into the German identity in ways that are both practical and surprisingly cosy.

And while beer may still dominate Oktoberfest, and wine holds a special place in regional identity, it’s coffee that fuels Germany’s mornings, afternoons and often late-night conversations. So next time you picture Germany, try imagining not just a land of steins and sausages, but also of steaming mugs, intricate espresso machines and generous slices of cake.

And now, excuse me if you will. While this love letter to German coffee culture lands in your inbox, I think I can hear beans being ground in the kitchen…

I'm more of a rooibos drinker first thing in the morning, something to do with the local Dutch influence if I mention coffee the reply is always Douwe Egberts ,which could well transition through Hamburg on its way to The Netherlands. In my role as postie I collect people's parcels and one of the most popular returns are aluminium coffee pods for recycling. The Tchibo factory near Heathrow always smells lovely when you drive past .

Over many years of coffee drinking I now have four “machines” or methods of making coffee (and instant). For me the process is part of the joy and different moods need different methods. Others in the household disagree…